ORIGINAL ARTICLE

PEREIRA, Jeremias [1], PITHAN, Lívia Haygert [2]

PEREIRA, Jeremias. PITHAN, Lívia Haygert. The relationship between public international law and petroleum law: Study of the case between Timor-Leste and Australia. Multidisciplinary Core scientific journal of knowledge. 04 year, Ed. 12, Vol. 02, pp. 31-51. December 2019. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link in: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/law/international-public-law

SUMMARY

This article aims to analyze the Law of the Sea and Petroleum to understand the reasons that generated, for more than a decade, the conflict between Timor-Leste and Australia regarding the definition of definitive maritime borders. Timor-Leste has already been exploited and invaded by several nations. Because of the abundance of oil and natural gas, it suffered to gain independence in 2002, as well as struggled to enjoy its maritime territory until 2018, from this new context of the maritime border treaty signed between Timor-Leste and the Australia. The median equidistance line was the parameter used to define the definitive Timorese borders, granting the right to enjoy their maritime territory. The definitive pact on borders has contributed greatly to the development of Timor-Leste, due to the exploitation of sea riches, in addition to recognizing the country’s need for oil companies to assist in the evolution of Timor-Leste in a specific and punctual way. This now needs to be ratified by the national parliaments of both countries. The ratification process is due to be completed in 2019. Timor-Leste is currently seeking to negotiate its maritime borders with Indonesia, but these have been suspended during the mandatory conciliation process with Australia. Now that this process is over, the two countries can resume their discussions again.

Keywords: Oil law, international law, sea law.

1. INTRODUCTION

For more than a decade, Australia and Timor-Leste have disagreed with the maritime borders of each of these states. The dispute takes place because of the right to oil exploration and other sea wealth and the obstacles to the economic and political development of Timor-Leste, after a treaty signed with Australia. Thus, this article develops in the area of public international law, specifically in the area of Petroleum Law.

It is questioned whether the treaty between Australia and Timor-Leste, on the definition of maritime borders, has been balanced, fully preserving the right of timorese. What are the obstacles to prevent this nation from being exploited disproportionately by other nations and can develop from 2019?

The relevance of this research is justified by the fact that the need to respect timor-leste’s maritime borders by Australia is justified. In the 21st century, despite the existence of international law and petroleum law, Australia had no interest in carrying out a Treaty in which timor-leste’s rights were recognised to receive the appropriate percentage for oil exploration of maritime territory. The country’s historical economic fragility with much lower land space than the seafarer has made it the target of exploitation of countries such as Indonesia and Australia. Although there has been a permanent Treaty between Timor-Leste and Australia in 2018, it is necessary to explore several legal documents dealing with Sea and Petroleum Law to build international legal foundations, with the aim of multiplying the instruments of defense against other nations that intend to unduly exploit the territorial space of Timor-Leste, due to the current economic fragility.[3]

Timor-Leste, until 1975, belonged to Portugal, its settlers. From 1976, Indonesia invaded him and began to exploit it, and only with the help of the United Nations (UN) this country elected its first president of the republic in 2001, becoming an independent state and member of the UN in 2002. Despite independence, Timor-Leste suffered from Australia’s tyranny by failing to receive financial resources for the exploitation of its maritime territory. Portugal, Indonesia and Australia have never invested properly in Timor-Leste, although they raised millions from oil extraction in that region, as well as other wealth. Due to decades of low financial investments, the Timorese nation needs to develop very politically and legally in order to occur in economic development.[4]

The general objective of this scientific paper is to analyze public international and petroleum law to understand the reasons that generated more than a decade ago the conflict between Timor-Leste and Australia on maritime borders. To understand the problem surrounding the maritime territory of Timor-Leste, several specific objectives have been outlined, such as

a) present an overview, political, historical, legal and economic vision of Timor-Leste and its relationship with Australia;

b) to examine international law relating to the Sea;

c) exploit the Right to Petroleum;

(d) analyse the treaty on the borders between Timor-Leste and Australia.

This article has its development divided into four parts: the possibilities of political-social, historical, legal and economic evolution of Timor-Leste will be analyzed throughout the research to achieve, analyze and verify whether the Treaty between Australia and Timor-Leste will in fact contribute to the advancement of Timorese society. From this information, it will be necessary to understand the reasons that led the people of Timor-Leste to have a low level of development in several areas.

The first chapter deals with the historical and geographical aspects, in addition to the exploitation of Timor-Leste by other nations, in a historical context, so that the reasons for the current legal, economic, political and social context of this country are understood.

In the second chapter, aspects are explored on the borders of the Timor-Leste Sea and the importance of international relations for that country. This analysis has the function of observing the factors that favor the Timorese people to be victimized by explorers again, due to their economic fragility today. To understand the mechanisms of defense of a State in relation to maritime attacks, it is necessary to address international law of the sea. This part of international law deals with internationally agreed standards and principles related to the property, use, exploitation and protection of the sea and its resources worldwide.[5]

In the Third chapter, the concept and importance of oil and its relevance to the development of nations that have a huge maritime territorial space and a small land space, such as Timor-Leste, will be explored.

Oil was discovered in the 19th century and, since its inception, there have been important transformations in humanity, It is a homogeneous mixture of organic compounds, mainly hydrocarbons, insoluble in water. This power source is also known as raw. Since 1859, it has been regarded as a preciousness and, in the 21st century, it is fiercely coveted for the relevant role it plays in the modern world. The rampant search for Australia and Indonesia for power and economic development has led to several conflicts with Timor-Leste because of the ambition of certain countries to exploit the maritime territory that did not belong to them. It is extremely important to understand how oil extraction occurs, as well as resources such as natural gas, to understand the reasons that led to undue exploitation for decades of Timorese oil. [6]

Subsequently, the obstacles to the development of Timor-Leste present in the fourth chapter. The relationship with the international community is extremely relevant for the development of this country. Advances in the legal and political sphere are essential for economic evolution. Companies responsible for exploiting the natural resources of the maritime territory must negotiate with prepared and trained Timorese professionals so that the agreements provide many advantages to Timor-Leste. [7]

The present study is not intended to exhaust all matters, but rather to stimulate discussions about the Conflict between Timor-Leste and Australia. The research technique used in this work will consist of bibliographic research, through analysis of doctrines, scientific articles, virtual libraries, as well as research in legal texts from websites recognized as information vehicles accredited by the government of Timor-Leste. The method adopted will be the inductive process by which the student, through the study of several positions of indoctrinators, will start from several particular understandings of certain authors, to reach several general conclusions. A bibliographic exploration will be carried out in relation to the subject, specifically, with each subchapter of the summary to achieve a general conclusion of the problem.[8]

2. TIMOR-LESTE, GEOGRAPHY, HISTORY, ECONOMY AND POLITICS

The Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste is a coastal country. Its main economic products are yams, corn, coffee, smoke, rubber, white sandalwood, cattle, pigs, buffalo, among others. This country is located on the island of Timor and has borders with Indonesia and Australia. Its territory corresponds to sections of this island, because in 1975, the time of independence of Portugal, the other half of the archipelago no longer belonged to the domain Portuguese. Because of this situation, there is currently a part of the island that is the territory of Indonesia. It is located in Southeast Asia, on the southern edge of the Indonesian archipelago, northwest of Australia, near Oceania. To the south, it is 250 to 400 nautical miles across the Timor Sea with the Australian mainland.

The maritime territory of this country, which has an abundance of oil and natural gas, has always attracted the greed of the various countries. Treaties and invasions that harmed timorese in various historical periods come from the desire to invade and take office to become a legitimate authority to carry out exploitation of the Timor-Leste Sea. In order to gain an advantage, Australia was the only country in the world that officially recognized the illegal annexation of Timor-Leste by Indonesia in the 1970s, although there is a resolution of the Security Council of the Assembly of the United Nations United nations that condemned this invasion.[9]

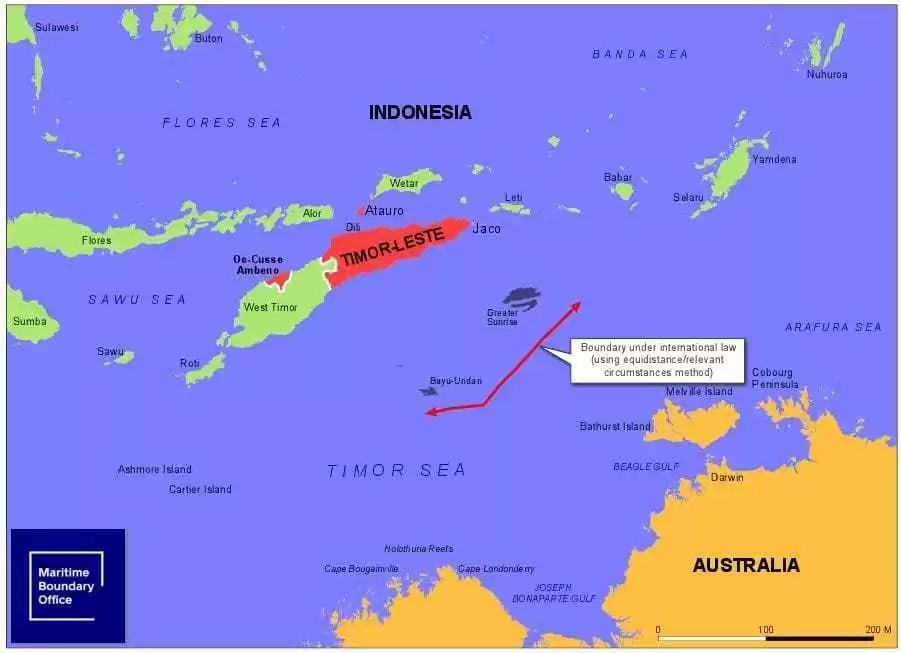

Figure 1 – Image caption Timor-Leste’s maritime borders

Indonesia, in July 1975, invaded Timor-Leste, remaining approximately for twenty-six years in that territory, at a time when many deaths from illness and food shortages occurred. The international community was moved by the genocide that occurred there. In 1999, the UN, together with Portugal, brokered an agreement with Indonesia, which dealt with the possibility of holding a referendum. In August 1999, Timorese opted for independence with a majority of votes, as 78% of the population no longer accepted the massacre they suffered. But the dominators did not accept liberation. Indonesian military personnel tortured and massacred the people. Many Timorese fled to the western part of the island, while everything that was built along the invasion was destroyed in that country. In order to control the massacre, the UN adopted Resolution 1246 of August 1999 to establish a multinational force to stabilize the situation. After the withdrawal from Indonesia, Timor-Leste became the recipient of aid from the international community, as there were human losses and incalculable materials. On May 20, 2002, with un aid, the independence of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste was restored, observing the first democratically elected government. [12]

Australia’s interest in Timor-Leste is nothing new. Australians had information that in the Timor-Leste Sea there was a lot of gas and oil. Since the discovery in 1960 that there has been wealth in the Timorese Sea foreign governments have tried to dominate the island. In the 1970s, Australia was the only country that recognized that the western half of the island of Timor belonged to Indonesia. It turns out that in 1970, an Australian company called Woodside Petroleum found a huge gas reserve in the region known as The Sunrise and Troubadour Fields or Greater Sunrise.[13] The intention to negotiate for territorial advantages was one of the reasons why Australians ignored the negative opinion of the international community, which did not agree with Indonesia’s conduct to invade the western part of the island of Timor. Interested in making profits from the discovery of wealth in the Timor-Leste Sea, Indonesia and Australia signed the treaty. This document concerned maritime borders between the two countries, but Australia took the territory in which gas reserves were located. Dissatisfied with the Treaty it signed in 1975 Indonesia invaded Australia to obtain a percentage on the exploitation of gas resources in that region. The Timorese did not agree with the treaty that shared the wealth of their territory between Indonesia and Australia, but the two foreign nations involved in the international agreement ignored the world’s position, contrary to their pact. On May 20, 2002, the date of the re-establishment of timor-leste independence, the country sought to take possession of the territory that was entitled to it. Timor no longer belonged to Indonesia. The treaties that had been agreed before independence were no longer valuable.[14]

Australia, in 2002, with the aim of remaining dominating the maritime territory that would belong to Timor-Leste, withdrew from all binding border procedures of which it was part. In 2006, there was a Treaty between Australia and Timor-Leste on Certain Maritime Adjustments in the Timor Sea, an agreement that displeased timorese because it served to avoid changes in legal negotiations or legal actions for fifty years. It was in 2016 that the people who felt harmed by the Treaty notified Australians that it would solve the problem of maritime borders by compulsory conciliation provided for in the UNITED NATIONS Convention, Article 298 and Annex V, which deals with Sea rights.[15]

The domination of Timor-Leste by other nations, in different historical periods, has greatly harmed it. Several reflections of the exploitation of Indonesia and Australia are felt in the development of the Timorese people in various areas. Since 2002, on the eve of Timor-Leste’s independence, Australians have withdrawn from several international treaties to prevent the loss of exploitation of the non-seaterritory. Australians and Timorese have separate territories for less than 400 nautical miles. Due to the proximity between the two nations, their maritime territories need to be defined in a peculiar and specific way, according to the principle of equity. It is essential to deepen knowledge about the law of the sea and oil to understand the reasons of fact and right that legitimize the struggle of the Timorese people for their maritime territory. [16]

3. RIGHT OF THE SEA AND OIL

The Law of the Sea belongs to international law, which observes the sovereignty and jurisdiction of states, defining the extent of their maritime domain. It also regulates several other topics such as the exploitation of existing resources on the bed and on the seabed, in addition to the preservation and conservation of the marine environment.[17] One of the greatest riches found at the bottom of the Timorese sea is Oil, which stands out for being a viscous, flammable black liquid, less dense than water. It consists of a mixture of hydrocarbons, molecules composed of Carbon and Hydrogen atoms, as well as molecules of Sulfur, Nitrogen, Oxygen and Metal Ions, and is located in natural underground reservoirs.[18]

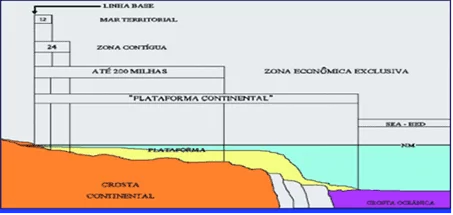

The Maritime Rights Conference took place in Geneva in 1958. In 1969, it was ratified by almost every country in the world. It deals with various subjects or topics that deal with the close connection in the ocean space between nations. The 1982 United Nations Convention on The Rights of the Sea (UNCLOS) was signed in Montego Bay, Jamaica, although it appeared at the Geneva conference. In this document are rules and principles of the territorial sea, contiguou[19]s, economic and continental areas.[20] With regard to the sovereignty of the coastal state over adjacent waters, it[21] regulates all countries that have adopted it, accepted or ratified it. There are also related standards on marine resource management and pollution control.[22]

THE UNDP determines that the sea of the coast has 12 nautical miles, that is, 22 km. At the vertical plane, it extends to airspace, having it as its limit. The seawater of the surface is limited through contact with the ocean bed, soil, as well as all subsoil is governed by the territorial sea legal regime.[23] The right of the sea to coastal states was guaranteed exclusive economic exploitation in an air of 200 nautical miles, but this rule does not apply to States that are less than 400 miles away from their contiguous areas.[24]

Figure 2 – Territorial sea

The Territorial Sea is the area located between the inland waters and the High Seas. It is the continuation of the sovereignty of a coastal country that exceeds its territory and its waters, according to Articles 2 and 3 of the UNCLOS.[25] The State exercises sovereignty over its territorial sea, airspace, as well as the bed and subsoil under the territorial sea, according to Art. 02 to 32 of the Convention on The Rights of the Sea.[26] The outer boundary of each nation’s territorial sea is twenty-two kilometers. The State exercises its jurisdiction over activities of national interest in the contiguous maritime area, which is set at 12 miles. The United Nations Convention created the Exclusive Economic Zone, EEZ, to balance interests between countries. This is an area located beyond the Territorial Sea. It refers to the area near the contiguous zone and extends up to 200 miles from the coast. The state has the right to navigate, fly over, install cables and marine ducts, as well as to exploit the minerals found in the soil and marine subsoil. Timor-Leste and Australia are separated by less than 400 miles away, and for this reason this rule does not solve conflicts over borders between the two nations.[27]

Timorese and Australians are peoples belonging to states with adjacent or situated front-to-face coasts. They do not meet the limits set by the United Nations Convention for the Application of The Rights of the Sea, related to the sovereignty of the State in the territorial sea. The distance from the coastal coast between the countries is 300 miles. These countries must delimit maritime borders by agreement, as determined by the rules of international law. Nations must achieve a fair, fair and equivalent solution.[28]

The Geneva Convention has criteria for parallel delimitation. The median line method is used in special circumstances for states with opposite backs. It regulates a readjustment of the median line between countries. The Convention on the Law of the Sea states that, in view of the lack of a distance of 400 miles for separation between two countries, the principle of equidistance should be used. [29]

The Oil Industry is extremely important. Today’s society depends on it and its derivatives. It is a fossil fuel, an electric energy source for most developed and developing countries. It is essential for manufacturing a range of products such as diesel, kerosene and gasoline. It is also present in inputs and in the petrochemical industry, through paraffin and naphtha. Many medicines have in their composition petroleum derivatives. It is impossible to reflect on the current molds of human life without asphalt, plastics and aspirin. Oil can be observed in fuels used for people’s locomotion. It is contained in a multitude of chemicals and petrochemicals fundamental to the development of a nation. Because of its vast applicability and because it is a exhausting source of energy, Australians have ignored International Sea law for many years. They withdrew from THE UNDP to prevent the Timorese people from being entitled to profits on the exploitation of oil companies Bayu Undan and Greater Sunrise.[30]

Due to the importance of oil, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) emerged in Vienna, Austria in 1960. The founding nations were the Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. Opec’s purpose is to establish a common policy for oil, protecting the incomes of producing countries. Before the creation of this organization, the oil exporting countries that held most of the oil reserves of the time benefited little. The huge corporations regulated the international oil market. The value of fossil fuel paid to producing countries and for resale to the final consumer was controlled by oil companies. The American companies Exxon, Texaco, Amoco and Chevro, as well as the Dutch Royal Dutch Shell and British Petroleum were called Seven Sisters. They carried out the exploration, refining, transportation and resale of oil, but only a small part of the fruits of the extraction was intended for the producing States. Currently, the United Nations also observes the actions of oil companies so that an appropriate agreement can occur between producing states and oil extractor companies.[31]

Timor-Leste has been explored for decades by Australia. This conduct was substantially driven by economic reasons, due to interest in the wealth of timorese sea territory. It is not new that the Oil Industry is motivated to remove Australia from the international community. Australians have not been willing to deal with matters related to the Rights of the Sea. Interest in profits over the extraction of oil and natural gas from the region belonging to Timor-Leste prevented there from reaching an agreement between the two nations for many years.[32]

Timorese have been harmed by Australia since independence in 2002. All oil and gas reserves are on the Timorese side of the median line, i.e. closer to Timor-Leste than to Australian territory. Australia no longer recognises the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea to delimit its borders on the median line with Timor-Leste months before its independence. Australia’s removal from THE UNDP had the intention of avoiding the loss or reduction of maritime territorial space, as it belonged by the right to the Timorese. The United Nations Convention on The Rights of the Sea states that each country must delimit as an exclusive economic zone 200 nautical miles, from the outer limit of its territorial sea, 12 miles from the coast. THE UNDP also deals with the great depths of the sea that are known as Area or Zone A, according to art. 1. This area is composed of marine and ocean bedand their subsoil.[33]

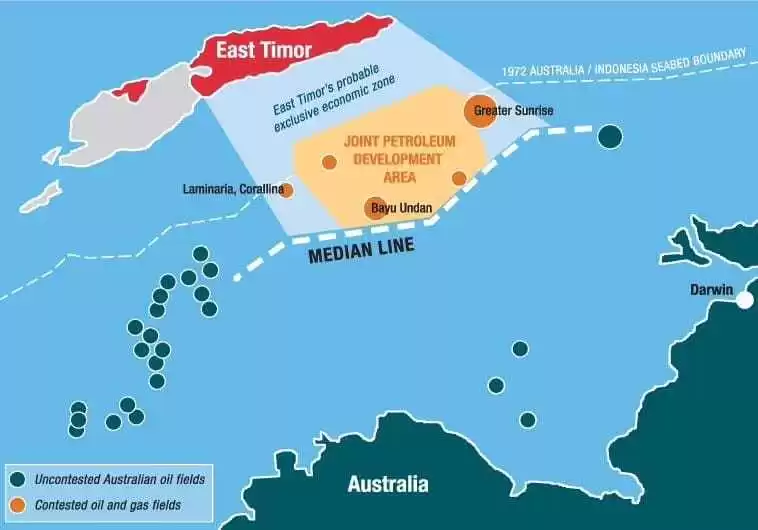

Figure 3 – Australia border demarcation line

Oil is a wealth that lies in abundance in Timor-Leste. The mediated line must be traced to define maritime space between two countries that separate for less than 400 nautical miles. Natural gas and oil reservoirs were found by Australian companies in Timor-Leste, before their independence. For this reason, Australians have had a lot of resistance to a definitive treaty on the right to exploitation of the Timorese Sea. The difficulties faced by these people to obtain their maritime rights are important issues. Analyzing the details that preceded the definitive treaty carried out in 2018, which deals with Timorese borders, is essential to understand the proportion of developments that this pact means. [36]

4. TREATY BETWEEN AUSTRALIA AND TIMOR-LESTE

In 2002, Timor-Leste gained its independence from Indonesia, but since that year, the definitive Maritime Borders of Timore have not been demarcated. Australians, for many years, have no interest in dealing with timor-leste maritime boundaries, observing international law standards. They intended to remain using the resources of the sea that did not belong to them. Although they caused damage to the development of Timor-Leste in several areas for a long time, the pact has not foreseen the compensation of the damage caused since 2002.[37]

The Timorese people will not be reimbursed for the damage caused to their evolution in the areas of education, social, economic, political, among others that require minimal financial resources to occur. But when the pact was carried out, it was observed that Timor-Leste has been greatly harmed over the years by Australia.[38] In order to encourage the development, industrial, technological and economic of timorese, it was agreed that the company that would carry out the exploration of Greater Sunrise would have to hire the citizens of Timor-Leste, facilitating them training encouraging the development of their studies, as well as it would have the duty to adopt the country as the first option for the acquisition of goods and services.[39]

In order to avoid economic loss, Australia withdrew from several International Treaties of which it was integral months before the independence of Timor-Leste.[40] In order to prevent either country from failing to observe the pact in the future, nations stipulated that the treaty would not be subject to a unilateral right to denunciation, withdrawal or suspension. In the text of the document, it was clarified that all clauses expressed in the treaty and annexes are part of the pact and cannot be ignored or highlighted. In the face of possible future dispute, it was agreed that it could be resolved with the help of the members of the Conciliation Commission who mediated the pact between the two nations in 2018. However, in the permanence of disagreement on the issues, issues addressed with the intervention of the members of the Conciliation Committee could be brought before the arbitral tribunal, and that second decision would have a binding effect.[41]

On March 6, 2018, the agreement between Timor-Leste and Australia took place. This pact delimits the continental basin. In this document, the median line and side borders were demarcated to the east and west of the old zone known as Timor Gap, according to art. 1st of timor-leste’s maritime border treaty.[42] From this new context, Timor-Leste becomes allowed to carry out the exploitation of marine soil resources such as oil and natural gas, in addition to providing the benefits to rights from the exclusive economic zone. This nation also gained the right to exploit other maritime resources such as fishing, enabling increased financial resources for the country. [43]

Figure 4 – Treaty of Australia and Timor-Leste on Timor’s borders

The ways that revenues would be shared between Timor-Leste and Australia were not defined, as they would depend on several factors. The greater the ability to develop techniques and apply them, the higher their profits would be. According to ways of exploring the Greater Sunrise fields, the results would be shared. In the year in which the pact occurred, it was agreed that oil field revenues would belong 30% to Australia and 70% for Timor-Leste if there was an increase in exploration through the development of gas pipeline for the Timorese people. It was also predicted that, in the event that the Greater Sunrise fields will be developed through a Pipeline to Australia, the percentages would be modified, belonging to 20% for Australians and 80% for Timorese.[46]

In the definitive treaty on borders, according to art. 12 of the legal document, it was defined that the exploration of gas and oil in the Greater Sunrise field region would depend on the definition between the parties on the development plan. It turns out that after the start of the exploration activities of the sea region that would have shared revenues, the contracted company would submit to the exclusive jurisdiction of the country where it is located. The Supervisory Board of two representatives from Timor-Leste and a representative from Australia would be established. In order to find solutions to litigation, there would be an Independent Conflict Resolution Committee for decisions on the strategies adopted for the exploration of the oil field referred to above.[47]

For decades, Australia has demonstrated its intention to make profits from the exploitation of oil fields in full. International intervention was needed to reduce the conflict over borders between Timorese and Australians. The definitive Treaty on Borders deals with the median line and lateral limits on the territory of Timor-Leste and shares revenues from an oil region between the countries involved. But this pact does not extinguish the possibility of future conflicts over profits from the Greater Sunrise fields. Many questions were pending clarification, requiring concrete conflicts to arise for positions to be adopted. Faced with this new situation, the Timorese people will face several obstacles so that they can enjoy all the possibilities for their development in various areas.[48]

5. THE OBSTACLES TO TIMOR-LESTE DEVELOPMENT

Timor-Leste is a maritime state and not just oil. There are several sectors that can contribute to the evolution of the nation. For many years it was explored by Portugal, Indonesia and Australia. Few resources have been invested in education and infrastructure. The nation has been harmed in the development of several areas due to Indonesia’s neglect. There are few professionals with technical, political, legal and administrative skills, because during the period of domination of the people, only foreign professionals were hired to perform activities in these areas.[49]

Figure 5 – Students from a school on the Timorese periphery

In the treaty document, standards involving large international explorer companies were established. Oil companies should contribute to timor-leste’s development by preferably hiring professionals, services and products in the country. Timorese will not only relate to representatives of the Australian government, but with experienced private-initiative resumming. Foreign representatives of the Australian government or private companies from various nations may have vast ability to negotiate and deal with inexperienced Timorese. Timor-Leste has professionals with little technical skill, but this situation should not compromise development. It will be the mission of these entrepreneurs to assist in the education and teaching of the skills and knowledge required of workers to perform tasks related to exploration activities. Increasing financial resources will contribute to the transformations of sectors, technical, administrative, political, legal, among others, facilitating the transposition of obstacles to the development of the nation.[52]

The exploration of gas and oil will require that the legislative power of Timor-Leste be aware of the emergence of new facts arising from this activity. State agencies will need to find quick responses to divergences between the state, representatives of exploitative companies and Australia. Although the contracted company has an obligation to submit to the exclusive jurisdiction of the country where it is located, the experience and ability of private sector representatives to manipulate the negotiations should be considered. It is undeniable that the government of Timor-Leste adopts positions that contribute to progress in various areas of the country, but it is a fact that the timorese executive, legislative and judicial powers are still developing, because it is a very young country.[53]

Timor-Leste has extensive experience in fighting, as the people organized against the invasion of Indonesia and obtained their independence.[54] Currently, it advances in search of providing education, infrastructure, economy, policy and adequate administrative management for citizens. In the pact on definitive borders, the fragility situation of Timor-Leste was recognized. And mechanisms to assist in the evolution of the country were positive in the agreement.[55]

The Government of Timor-Leste will have complex tasks, and a legal and administrative sector prepared to act in new activities will be necessary. Reports and development plans on the exploration of the Bayu-Undan, Buffalo and Kitan fields will need to be issued during the transition period of exploration of that region. This duty will require specific technical knowledge about oil and gas exploration.[56] Many sectors are related to the development of a nation. Investment policies in sectors that have renewable sources of exploitation need to be observed by the Government of Timor-Leste. The provisions of the Pact on Timorese borders, related to the duty of companies to assist in the evolution of various sectors should be considered. The State will have to strive for development to the same extent that it should require private initiative to contribute to the country’s evolution.[57]

Economic growth is critical for progress in infrastructure, policy and administration. Timor-Leste’s economic rise is linked to the agriculture, tourism and sea sectors and not just oil and gas exploration. Agriculture is essential for Timor-Leste, as well as has great relevance to several other nations. From it is that food is produced. Primary products from agriculture can be used by industries, trade and the service sector. They can become the basis for maintaining the national and international economy.[58]

The exploration of the maritime economy is also crucial for the evolution of the Timorese nation. Many people depend on the sea and support themselves with the resources generated by fishing and harvesting marine species. It turns out that, in the maritime territory of that country, there is a natural passage of fish. And through the developments brought by the definitive pact on borders, several species of fish could be exploited by national industries. In addition to the increase in revenue for the emergence of industries interested in the many species of schools that that region has, this nation is located in the Coral Triangle. This is a cultural heritage that can be appreciated by tourism, as well as it can serve as an interest to scientific research. The above characteristics may generate the direct and indirect increase in resources for the State, provided that appropriate administrative measures occur.[59]

The infrastructure of Timorese ports and airports is also fundamental for country growth. The parameters of strategic constructions must monitor the needs of navigations of the global scenario that the Timorese territory may transit through the Timorese territory. The ports of Dili, Oe-cusse, Hera, Caravela and Com currently have inadequate characteristics, requiring investments to be considered as industrial centers. This evolution will create opportunities for Timor-Leste to become a transit of oil tanker cargo, as well as making it a nation possessing a large industrial hub that connects the Pacific and Indian Oceans.[60]

Timor-Leste needs to continue advancing in many areas. The agricultural, oil, maritime, tourist, educational, legal, political and economic sectors need transformations. There is already a development policy plan that was created in 2011. However, it is necessary to adapt it to the new reality in which the country is located, after the changes that occurred by the definition of its final maritime borders.[61] Specific strategies for each sector will need to be retraced on an internal national level. And, based on these new objectives, the positions with oil and gas exploration companies should be adopted, just as all decisions of the State will be in order to achieve these growth goals.[62]

6. CONCLUSION

Timor-Leste is located in Southeast Asia and is a very young country, which gained its independence in 2002. It is indonesia’s neighbor, which lies to the north, and to the south is Australia. It has a nation characterized by its strength and struggle. This warrior and suffering people communicate through the Portuguese language and Tetum, officially, but in the territory there are more than 14 native languages. It was colonized by Portugal and invaded by Indonesia in 1975. It has a treasure located in its maritime territory, due to the oil and natural gas that in the Timorese sea meet. These riches of Timor-Leste were the subject of a battle with Australia. Disagreement between Australians and Timorese began months before the independence of Timor-Leste of Indonesia. Australia had no interest in negotiating, as provided for by International Sea law, to avoid the loss of revenue stemming from the Timorese sea. But in 2018, a Definitive Treaty on Timor-Leste’s borders was held with Australians. This was the historical moment when the nation obtained recognition of the right to enjoy its territorial sea.

The country’s delicate economic situation was recognized in the Timor-Leste’s definitive Border Treaty. The scarcity of economic resources is related to the exploitation of this nation in a devastating way. Portugal invested little during the period of over 400 years in which this country was its colony. After being released from Portuguese domination, a new attack on Timor-Leste took place. For more than twenty-four years, timorese suffered from the occupation of Indonesia, but small investments were made. However, from the period when the Timorese people showed interest in fighting for their independence, everything was destroyed by the Indonesian people. In the initial phase of the occupation of Timor-Leste by Indonesia, the international community contributed aid to the country’s basic reconstruction.

The independence of the Timorese did not give them the immediate right to take possession of the maritime wealth that belonged to them, due to the fact that they were on their territory. Interim agreements on borders, pacts that harmed timorese were held with Australia before 2018. Since 2002, Timor-Leste has claimed ownership of its maritime territory, as provided for in the international law standards, UNCLOS/1982. It turns out that a few months before Timor-Leste gained its independence, Australia withdrew from several international pacts.

Since the maritime territories of Timor-Leste and Australia separated by a distance of less than 400 nautical miles, a short distance between the territories of the two nations, the border delimitation line adopted was defined by the standard of equidistance and median line. This is the model provided for in the 1982 United Nations Convention on The Rights of the Sea, used to resolve conflicts that have been over territories that distance themselves for less than 400 nautical miles.

Australians have avoided reaching an agreement with timorese on definitive borders, in accordance with the rules of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Sea for many years. The purpose of this stance was to disrespect the way of delimiting maritime borders, which provides as standard the adoption of the median line and equidistance in specific conflicts over definition of borders. The reason for Australia’s removal from the international community is related to the extension of profit from the exploitation of the sea that belongs to the Timorese people.

After several attempts to definitively agree on Timorese borders with Australia, the country succeeded. Clearly and specifically, in a document that has more than 11 articles, permanent bilateral maritime borders were addressed along an essentially equidistant line between the two nations. Timor-Leste had its borders delimited as provided for in the United Nations Convention on The Law of the Sea. It was agreed in the treaty that there is an indivisible link between the maritime border of Timor-Leste and Australia. There was recognition of the existence of a maritime area belonging to the two nations involved in the pact.

During the preparation of the document, the parties shared revenues from the exploitation of greater sunrise fields and positive in the text of the international pact the need to draw up rules dealing with the exploitation of the fields of the region belonging to the two Countries. It has been established that the rules agreed in the Treaty or in its annexes may not be partially unobserved by any of the parties involved. It was also regulated that sea wealth exploration plans need to be created before the procedures begin, as well as it was also agreed that oil companies would need to purchase products and services preferably from the Timorese people.

Timor-Leste’s definitive border pact is not only a common agreement between the governments of two nations. This timorese and Australian pact also covers obligations for private initiative. Duties have been allocated to companies that will carry out oil and gas exploration in the Greater Sunrise fields region. They should contribute to the development of Timor-Leste.

Many obstacles have needed to be removed so that Timor-Leste can develop widely, despite having earned the right to explore its maritime territory. Oil and gas are non-renewable resources, that is, they are sources of income with an estimated termination. But they are sources of immediate and profitable income. The development of education, infrastructure, agriculture, tourism and service delivery is essential for building a solid and renewable medium- and long-term income base. The country faces several obstacles such as little infrastructure and low level of education, but has been growing a lot since 2002.

In a capitalist world, it is undeniable that financial resources are determining factors for a nation’s broad evolution. The increase in revenues from oil and gas exploration will increase financial revenues, a fact that will contribute to developments in education and investments in the infrastructure of Timor-Leste ports and airports. If, before the Treaty on definitive borders, education, infrastructure, agriculture and industrial fisheries were obstacles to the development of timorese, it is expected that, after the definitive pact with Australia, this reality will be modified.

REFERENCES

BRASIL. Decreto nº 99.165, de 12 de março de 1990. Convenção das Nações Unidas sobre o Direito do Mar. Brasília: Planalto, 1990. Disponível em: https://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/decret/1990/decreto-99165-12-marco-1990-328535-publicacaooriginal-1-pe.html. Acesso em 15 abr.19.

DEL’OMO, Florisbal de Souza. Curso de direito internacional público. Rio de Janeiro: Forense, 2006.

GIBERTONI, Carla Adriana Comitre. Teoria e prática do direito marítimo. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar, 1998.

GOMES, Danaciano. Timor Leste: A economia do mar: um contributo para desenvolvimento sustentável. Aveiro: Mare Liberum, 2016.

GUSMÃO, Kay Raia Xanana. Breve história do mar do Timor. In: GOVERNO DO ESTADO DO TIMOR LESTE. Novas Fronteiras: conciliação histórica das fronteiras marítimas no mar do timor. Dili: Gabinete das Fronteiras marítimas, 2018.

MARCONI, Maria de Andrade, Lakatos, Eva, Maria. Fundamentos da metodologia cientifica. São Paulo: Atlas. 2003.

MARITIME BOUNDARY OFFICE. New frontiers: Timor-Leste’s historic conciliation on maritime boundaries in the timor sea. [S. l.], 2015. Disponível em: http://www.gfm.tl/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Website-map-of-Timor-Sea.pdf. Acesso em: 04 maio 2019.

MATTOS, Adherbal. Meira. O novo direito do mar. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar. 1996.

PEREIRA, Eliana Sofia da Silva. Contributo crítico para a compreensão do regime do Mar de Timor à luz do Direito Internacional. 2013. 87 f. Dissertação. (Mestrado em Ciências Jurídicas Internacionais) Faculdade de direito- Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2013. p.14. Disponível em: https://run.unl.pt/bitstream/10362/17481/1/Pereira_2013.pdf. Acesso em: 01 abr. 2019.

REPÚBLICA DEMOCRÁTICA DE TIMOR-LESTE. Ministério das finanças. Orçamento geral do Estado 2018. Díli: Gabinete Ministerial, 2018. p. 7. Disponível em: https://www.mof.gov.tl/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/BB5_Port.pdf. Acesso em: 15 maio 2019.

REPUBLICA DEMOCRÁTICA DO TIMOR LESTE. História do Timor Leste. Governo do Timor Leste, Dili, [s. d.]. Disponível em: http://timor-leste.gov.tl/?p=29&lang=pt. acesso em: 05 maio 2019.

REZEK, José Francisco. Direito internacional público: curso elementar. 10. ed. rev. e atual. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2005.

RIBEIRO, Marilda, Rosado de Sá. Direito do petróleo. 3. ed. rev. atual. e ampl. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar, 2018.

TIMOR LESTE; AUSTRÁLIA. Tratado sobre fronteiras marítimas entre Timor Leste e Austrália que estabelece as respectivas fronteiras do mar do Timor Leste. Nova York: [s.n.], 2018. p. 1. Disponível em: http://www.gfm.tl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Port-Timos-Sea-Maritime-Boundary-Treaty_Portuguese.pdf. Acesso em:04 maio 2018.

TIMOR SEA JUSTICE. All of the contested oil & gas fields are on EastTimor’s side of the median line ie closer to #Timor than Australia. Dili, 01 mar. 2016. Tiwitte: @timor sea justice. Disponível em: https://twitter.com/TimorSeaJustice/status/704895304701763584. Acesso em: 25 maio. 2019.

ZANELLA, T. V. Curso de direito do mar. Curitiba: Juruá, 2013.

APÊNDICE – REFERENCIAS DE NOTA DE RODAPÉ

3. GOMES, Danaciano. Timor-Leste: A economia do mar: um contributo para desenvolvimento sustentável. Aveiro: Mare Liberum, 2016.

4. GUSMÃO, Kay Raia Xanana. Breve história do mar do Timor. In: GOVERNO DO ESTADO DO TIMOR LESTE. Novas Fronteiras: conciliação histórica das fronteiras marítimas no mar do timor. Dili: Gabinete das Fronteiras marítimas, 2018. p. 6.

5. RIBEIRO, Marilda, Rosado de Sá. Direito do Petróleo. 3. ed. rev. atual. e ampl. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar, 2018.

6. RIBEIRO, Marilda, Rosado de Sá. Direito do Petróleo. 3. ed. rev. atual e ampl. Rio de Janeiro Renovar, 2018.

7. GOMES, Danaciano. Timor Leste: a economia do mar: um contributo para desenvolvimento sustentável. Aveiro: Mare Liberum, 2016.

8. MARCONI, Maria de Andrade, Lakatos, Eva, Maria. Fundamentos da metodologia cientifica. São Paulo: Atlas. 2003.

9. GUSMÃO, Kay Raia Xanana. Breve história do mar do Timor. In: GOVERNO DO ESTADO DO TIMOR LESTE. Novas Fronteiras: conciliação histórica das fronteiras marítimas no mar do timor. Dili: Gabinete das Fronteiras marítimas, 2018. p. 7-8.

10. MARITIME BOUNDARY OFFICE. New frontiers: Timor-Leste’s historic conciliation on maritime boundaries in the timor sea. [S. l.], 2015. Disponível em: http://www.gfm.tl/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Website-map-of-Timor-Sea.pdf. Acesso em: 04 maio 2019.

11. GOMES, Danaciano. Timor Leste: A economia do mar: um contributo para desenvolvimento sustentável. Aveiro: Mare Liberum, 2016. p. 35-36.

12. GOMES, Danaciano. Timor Leste: A economia do mar: um contributo para desenvolvimento sustentável. Aveiro: Mare Liberum, 2016. p. 37 e 38

13. PEREIRA, Eliana Sofia da Silva. Contributo crítico para a compreensão do regime do Mar de Timor à luz do Direito Internacional. 2013. 87 f. Dissertação. (Mestrado em Ciências Jurídicas Internacionais) Faculdade de direito- Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2013. p.14. Disponível em: https://run.unl.pt/bitstream/10362/17481/1/Pereira_2013.pdf. Acesso em: 01 abr. 2019.

14. PEREIRA, Eliana Sofia da Silva. Contributo crítico para a compreensão do regime do Mar de Timor à luz do Direito Internacional. 2013. 87 f. Dissertação. (Mestrado em Ciências Jurídicas Internacionais) Faculdade de direito- Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2013. p.14. Disponível em: https://run.unl.pt/bitstream/10362/17481/1/Pereira_2013.pdf. Acesso em: 01 abr. 2019.

15. TIMOR LESTE; AUSTRÁLIA. Tratado sobre Fronteiras Marítimas entre Timor Leste e Austrália que estabelece as respectivas fronteiras do mar do Timor Leste. Nova York: [s.n.], 2018. p. 1. Disponível em: http://www.gfm.tl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Port-Timos-Sea-Maritime-Boundary-Treaty_Portuguese.pdf. Acesso em:04 maio 2018.

16. PEREIRA, Eliana Sofia da Silva. Contributo crítico para a compreensão do regime do Mar de Timor à luz do Direito Internacional. 2013. 87 f. Dissertação. (Mestrado em Ciências Jurídicas Internacionais) Faculdade de direito- Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2013. p.14. Disponível em: https://run.unl.pt/bitstream/10362/17481/1/Pereira_2013.pdf. Acesso em: 01 abr. 2019.

17. MATTOS, Adherbal. Meira. O novo Direito do Mar. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar. 1996. p. 04

18. RIBEIRO, Marilda, Rosado de Sá. Direito do Petróleo. 3. ed. rev. atual. e ampl. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar, 2018.

19. Zona Contígua é Faixa entre o mar territorial e o alto-mar, fixada entre 12 e 24 milhas, na qual o Estado exerce sua jurisdição sobre atividades marítimas e sobre diversos interesses nacionais.

20. Plataforma continental é definida como uma faixa de terra submersa, em toda a extensão do litoral do continente. Geralmente, a plataforma possui uma extensão de 70 a 90 km, e profundidade de 200 metros, até atingir as bacias oceânicas.

21. Nota explicativa: Águas adjacentes são aquelas que banham as margens do território de uma nação.

22. ZANELLA, T. V. Curso de Direito do Mar. Curitiba: Juruá, 2013.

23. ZANELLA, T. V. Curso de Direito do Mar. Curitiba: Juruá, 2013.

24. RIBEIRO, Marilda, Rosado de Sá. Direito do Petróleo. 3. ed. rev. atual. e ampl. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar, 2018.

25. REZEK, José Francisco. Direito Internacional Público: curso elementar. 10. ed. rev. e atual. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2005. p.307

26. BRASIL. Decreto nº 99.165, de 12 de março de 1990. Convenção das Nações Unidas sobre o Direito do Mar. Brasília: Planalto, 1990. Disponível em: https://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/decret/1990/decreto-99165-12-marco-1990-328535-publicacaooriginal-1-pe.html. Acesso em 15 abr.19.

27. GIBERTONI, Carla Adriana Comitre. Teoria e prática do direito marítimo. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar, 1998. p.33.

28. GOMES, Danaciano. Timor Leste: A economia do mar: um contributo para desenvolvimento sustentável. Aveiro: Mare Liberum, 2016. p.51

29. PEREIRA, Eliana Sofia da Silva. Contributo crítico para a compreensão do regime do Mar de Timor à luz do Direito Internacional. 2013. 87 f. Dissertação. (Mestrado em Ciências Jurídicas Internacionais) Faculdade de direito- Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2013. p.56. Disponível em: https://run.unl.pt/bitstream/10362/17481/1/Pereira_2013.pdf. Acesso em: 01 abr. 2019.

30. GOMES, Danaciano. Timor Leste: A economia do mar: um contributo para desenvolvimento sustentável. Aveiro: Mare Liberum, 2016. p.110 e 111

31. RIBEIRO, Marilda, Rosado de Sá. Direito do Petróleo. 3. ed. rev. atual. e ampl. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar, 2018. P. 74 à 80

32. GUSMÃO, Kay Raia Xanana. Breve história do mar do Timor. In: GOVERNO DO ESTADO DO TIMOR LESTE. Novas Fronteiras: conciliação histórica das fronteiras marítimas no mar do timor. Dili: Gabinete das Fronteiras marítimas, 2018.

33. DEL’OMO, Florisbal de Souza. Curso de Direito Internacional Público. Rio de Janeiro: Forense, 2006. p. 292.

34. TIMOR SEA JUSTICE. All of the contested oil & gas fields are on EastTimor’s side of the median line ie closer to #Timor than Australia. Dili, 01 mar. 2016. Tiwitte: @timor sea justice. Disponível em: https://twitter.com/TimorSeaJustice/status/704895304701763584. Acesso em: 25 maio. 2019.

35. GUSMÃO, Kay Raia Xanana. Breve história do mar do Timor. In: GOVERNO DO ESTADO DO TIMOR LESTE. Novas Fronteiras: conciliação histórica das fronteiras marítimas no mar do timor. Dili: Gabinete das Fronteiras marítimas, 2018. p. 34 e 35

36. DEL’OMO, Florisbal de Souza. Curso de Direito Internacional Público. Rio de Janeiro: Forense, 2006. p. 292

37. DEL’OMO, Florisbal de Souza. Curso de Direito Internacional Público. Rio de Janeiro: Forense, 2006. p. 292

38. REPUBLICA DEMOCRÁTICA DO TIMOR LESTE. História do Timor Leste. Governo do Timor Leste, Dili, [s. d.]. Disponível em: http://timor-leste.gov.tl/?p=29&lang=pt. acesso em: 05 maio 2019.

39. TIMOR LESTE; AUSTRÁLIA. Tratado sobre Fronteiras Marítimas entre Timor Leste e Austrália que estabelece as respectivas fronteiras do mar do Timor Leste. Nova York: [s.n.], 2018. p. 1. Disponível em: http://www.gfm.tl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Port-Timos-Sea-Maritime-Boundary-Treaty_Portuguese.pdf. Acesso em:05 maio 2018.

40. PEREIRA, Eliana Sofia da Silva. Contributo crítico para a compreensão do regime do Mar de Timor à luz do Direito Internacional. 2013. 87 f. Dissertação. (Mestrado em Ciências Jurídicas Internacionais) Faculdade de direito- Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2013. p.14-15. Disponível em: https://run.unl.pt/bitstream/10362/17481/1/Pereira_2013.pdf. Acesso em: 01 abr. 2019

41. TIMOR LESTE; AUSTRÁLIA. Tratado sobre Fronteiras Marítimas entre Timor Leste e Austrália que estabelece as respectivas fronteiras do mar do Timor Leste. Nova York: [s.n.], 2018. p. 1. Disponível em: http://www.gfm.tl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Port-Timos-Sea-Maritime-Boundary-Treaty_Portuguese.pdf. Acesso em:05 maio 2018.

42. TIMOR LESTE; AUSTRÁLIA. Tratado sobre Fronteiras Marítimas entre Timor Leste e Austrália que estabelece as respectivas fronteiras do mar do Timor Leste. Nova York: [s.n.], 2018. p. 1. Disponível em: http://www.gfm.tl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Port-Timos-Sea-Maritime-Boundary-Treaty_Portuguese.pdf. Acesso em:05 maio 2018.

43. GIBERTONI, Carla Adriana Comitre. Teoria e prática do direito marítimo. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar, 1998. p. 33.

44. TIMOR LESTE; AUSTRÁLIA. Tratado sobre Fronteiras Marítimas entre Timor Leste e Austrália que estabelece as respectivas fronteiras do mar do Timor Leste. Nova York: [s.n.], 2018. p. 1. Disponível em: http://www.gfm.tl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Port-Timos-Sea-Maritime-Boundary-Treaty_Portuguese.pdf. Acesso em:05 maio 2018.

45. TIMOR LESTE; AUSTRÁLIA. Tratado sobre Fronteiras Marítimas entre Timor Leste e Austrália que estabelece as respectivas fronteiras do mar do Timor Leste. Nova York: [s.n.], 2018. p. 1. Disponível em: http://www.gfm.tl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Port-Timos-Sea-Maritime-Boundary-Treaty_Portuguese.pdf. Acesso em:05 maio 2018.

46. TIMOR LESTE; AUSTRÁLIA. Tratado sobre Fronteiras Marítimas entre Timor Leste e Austrália que estabelece as respectivas fronteiras do mar do Timor Leste. Nova York: [s.n.], 2018. p. 1. Disponível em: http://www.gfm.tl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Port-Timos-Sea-Maritime-Boundary-Treaty_Portuguese.pdf. Acesso em:05 maio 2018.

47. TIMOR LESTE; AUSTRÁLIA. Tratado sobre Fronteiras Marítimas entre Timor Leste e Austrália que estabelece as respectivas fronteiras do mar do Timor Leste. Nova York: [s.n.], 2018. p. 1. Disponível em: http://www.gfm.tl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Port-Timos-Sea-Maritime-Boundary-Treaty_Portuguese.pdf. Acesso em:05 maio 2018.

48. GOMES, Danaciano. Timor Leste: A economia do mar: um contributo para desenvolvimento sustentável. Aveiro: Mare Liberum, 2016. p. 59.

49. REPUBLICA DEMOCRÁTICA DO TIMOR LESTE. História do Timor Leste. Governo do Timor Leste, Dili, [s. d.]. Disponível em: http://timor-leste.gov.tl/?p=29&lang=pt. Acesso em: 05 maio 2019.

50. O PRIMEIRO dia no Timor Leste. In: PARCEIROS pela paz. Dili, 06 jul. 2011. Disponível em: https://parceirospelapaz.wordpress.com/category/timor-leste/. Acesso em: 25 maio 2019.

51. REPÚBLICA DEMOCRÁTICA DE TIMOR-LESTE. Ministério das finanças. Orçamento geral do Estado 2018. Díli: Gabinete Ministerial, 2018. p. 7. Disponível em: https://www.mof.gov.tl/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/BB5_Port.pdf. Acesso em: 15 maio 2019.

52. TIMOR LESTE; AUSTRÁLIA. Tratado sobre Fronteiras Marítimas entre Timor Leste e Austrália que estabelece as respectivas fronteiras do mar do Timor Leste. Nova York: [s.n.], 2018. p. 1. Disponível em: http://www.gfm.tl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Port-Timos-Sea-Maritime-Boundary-Treaty_Portuguese.pdf. Acesso em: 19 maio 2018.

53. GOMES, Danaciano. Timor Leste: A economia do mar: um contributo para desenvolvimento sustentável. Aveiro: Mare Liberum, 2016.

54. REPUBLICA DEMOCRÁTICA DO TIMOR LESTE. História do Timor Leste. Governo do Timor Leste, Dili, [s. d.]. Disponível em: http://timor-leste.gov.tl/?p=29&lang=pt. acesso em: 05 maio 2019

55. TIMOR LESTE; AUSTRÁLIA. Tratado sobre Fronteiras Marítimas entre Timor Leste e Austrália que estabelece as respectivas fronteiras do mar do Timor Leste. Nova York: [s.n.], 2018. p. 1. Disponível em: http://www.gfm.tl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Port-Timos-Sea-Maritime-Boundary-Treaty_Portuguese.pdf. Acesso em: 19 maio 2018.Acessado: 05/05/19

56. TIMOR LESTE; AUSTRÁLIA. Tratado sobre Fronteiras Marítimas entre Timor Leste e Austrália que estabelece as respectivas fronteiras do mar do Timor Leste. Nova York: [s.n.], 2018. p. 1. Disponível em: http://www.gfm.tl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Port-Timos-Sea-Maritime-Boundary-Treaty_Portuguese.pdf. Acesso em:05 maio 2018.

57. TIMOR LESTE; AUSTRÁLIA. Tratado sobre Fronteiras Marítimas entre Timor Leste e Austrália que estabelece as respectivas fronteiras do mar do Timor Leste. Nova York: [s.n.], 2018. p. 1. Disponível em: http://www.gfm.tl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Port-Timos-Sea-Maritime-Boundary-Treaty_Portuguese.pdf. Acesso em:05 maio 2018.

58. GOMES, Danaciano. Timor Leste: A economia do mar: um contributo para desenvolvimento sustentável. Aveiro: Mare Liberum, 2016

59. GOMES, Danaciano. Timor Leste: A economia do mar: um contributo para desenvolvimento sustentável. Aveiro: Mare Liberum, 2016. p.114-115.

60. GOMES, Danaciano. Timor Leste: A economia do mar: um contributo para desenvolvimento sustentável. Aveiro: Mare Liberum, 2016.

61. REPÚBLICA DEMOCRÁTICA DE TIMOR-LESTE. Ministério das finanças. Orçamento geral do Estado 2018. Díli: Gabinete Ministerial, 2018. Disponível em: https://www.mof.gov.tl/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/BB5_Port.pdf. Acesso em: 15 maio 2019.

62. GOMES, Danaciano. Timor Leste: A economia do mar: um contributo para desenvolvimento sustentável. Aveiro: Mare Liberum, 2016.

[1] Academic Law School, School of Law, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul – PUC-RS.

[2] Guidance counselor. PhD in Private Law. Master’s degree in law. Law degree.

Submitted: August, 2019.

Approved: December, 2019.