ORIGINAL ARTICLE

RODRIGUES, Adevanio Penote [1]

RODRIGUES, Adevanio Penote. The importance of agribusiness in the United States in promoting food security. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year. 08, Ed. 01, Vol. 03, pp. 53-75. January 2023. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/agronomy-en/importance-of-agribusiness, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/agronomy-en/importance-of-agribusiness

ABSTRACT

The expression “food security” appears at the end of the 2nd. World War, before the misery installed in different countries. In opposition to food security that guarantees a dignified survival, there is food insecurity, represented by the lack of basic inputs for a diet that guarantees energy and vitality to individuals. Food insecurity around the world is on a vertiginous scale, aggravated by the Covid-19 pandemic. Global hunger is caused by different factors: population growth; social differences; more or less extreme weather events; constant rises in food prices; insufficient demand and distribution to the most needy regions; among other structural and conjunctural deficiencies. To combat this humanitarian tragedy, the forms of cultivation and production in agriculture evolved to version 5.0, bringing new practices and cutting-edge equipment to the field. This article was developed, according to the methodology of bibliographical research, aiming to answer the question: how does the modernization of North American agribusiness collaborate with the fight against food insecurity? The objective is to present the modernization of existing planting techniques and possible improvements, based on Agriculture 5.0. As a result of the analysis and interpretation of the selected literature, it was found that the adoption of new technologies arising from Agriculture 5.0 optimize all planting and food cultivation practices, from the collection of information in real time through drones, and interpretation of the data received in computers that make possible the purchase, use and control of inputs, pest control, optimization of the harvest and its greater use.

Keywords: Food Crisis, Food (In)Security, Decarbonization, Agricultural Management, Agriculture 5.0.

1. INTRODUCTION

Hunger is linked to food insecurity that permeates people’s lives. According to Gaspari (2001, p. 7), “global hunger, also called energy or caloric hunger, is understood as the inability of the daily food ration ingested by a person to provide calories equivalent to the energy spent by the body in the work carried out”.

The expression “food security” appears at the end of the 2nd. World War, becoming a military term linked to national security, until the 1970s (OXFAM BRASIL, 2021). At that time, it was found that, far beyond the war arsenal that different nations could accumulate, to lead the world, it is necessary for a country to be able to develop its capacity to produce and supply the food necessary for the survival of a given population, or that can be provided to other locations that need them (FUNDAÇÃO CARGILL, 2022).

There are several problems that enhance global food insecurity, given the “contradictions between socioeconomic conditions and production policies, given their historical evolution”, affecting the production and distribution of food. Evgenievich (2020), describes, as consequences, the situations: destruction of the environment; increase in social inequalities; unequal distribution and consumption of food in different regions and countries; demographic, environmental, energy and raw material issues.

In turn, there are data tabulated by different international organizations involved with the guarantees of life and survival of individuals, which show that, in 2013, “food insecurity affected 925 million people around the world, of which 800 million they were in the field”, which, in itself, is already a great paradox (BELIK and CAPACLE CORREA, 2013, p. 1).

In this regard, the same authors defend the existence of different factors that contribute to this situation, including population growth, weather events, the constant rise in food prices, insufficient demand and distribution to the most needy regions, inequalities social – which prevent millions of needy people from accessing employment and, therefore, healthy eating -, among other structural and conjunctural deficiencies (BELIK and CAPACLE CORREA, 2013, p. 1).

In turn, Marini (2022), reports the report issued by the United Nations (UNICEF, 2022), where it was shown that, in 2021, there were 2.3 billion people in moderate or severe food insecurity.

In this way, food production emerges as a basic pillar for the entire earthly sphere, with regard to both the guarantee of local production and supply, as well as localities located in different regions of the world. In this perspective, agriculture 5.0 and new cutting-edge technologies are inserted for the necessary improvements in the production of healthy foods, optimizing planting and harvesting practices, with greater agility, precision and economy.

This scientific article was developed from a survey of the specialized literature on the subject in question, constituting a bibliographical research, which aims to answer the question: how does the modernization of North American agribusiness collaborate with the fight against food insecurity? The objective of this study is to present the modernization of existing planting techniques and possible improvements, based on Agriculture 5.0.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A bibliographic review was carried out from the research of national and international journals, using articles published in Portuguese and English. The articles selected to compose this research were obtained from the Google Scholar database. The descriptors used for electronic searches were: agriculture, planting techniques, agribusiness and food security.

3. THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

3.1 FOOD SAFETY AND INSECURITY

According to the definition given by the National Council for Food and Nutrition Security, food is “a right of all individuals to have regular and permanent access to quality food and in sufficient quantity, without compromising other essential needs for their survival”, and which are based on good dietary practices (FUNDAÇÃO CARGILL, 2022).

Hunger is “the situation in which a person is, for a prolonged period, in need of food that provides the calories (energy) and nutritional elements necessary for the life and health of his organism” (GASPARI, 2001, p. 7 ). With this definition, the author explains that human beings need to have food at hand that contains “nutritive elements such as proteins, vitamins and mineral salts, which will fulfill their proper functions in terms of restoring cells, tissues and organs throughout the body” .

In this perspective, to define Food Security it is necessary to refer to the importance of fundamental actions, which are inherent to all world leaders, in the sense of permanently guaranteeing the production and supply of food in quantity and nutritional quality, which it must be admittedly proven by Organs regulatory bodies, as well as by the legal and supervisory rules in health and hygiene (FUNDAÇÃO CARGILL, 2022).

According to the Industrial Aviculture portal (AISI, 2020),

A segurança alimentar é definida como o estado em que as pessoas têm acesso físico, social e econômico a alimentos suficientes e nutritivos que atendam às suas necessidades alimentares para uma vida saudável e ativa. Essa definição é internacionalmente aceita e foi estabelecida na Cúpula Mundial da Alimentação de 1996.

In view of the above, it is inferred that the literature demonstrates that it is up to different nations to guarantee to all individuals – regardless of their ethnicity and/or geographic location – the right to meet their basic needs, which are care for their physical and mental health.

On the other hand is food insecurity. According to Kepple and Segall-Corrêa (2011, p. 187), “food and nutritional insecurity is seen as having consequences for health and well-being, which may or may not be expressed in physical-biological consequences, such as low weight and/or nutritional deficiencies”.

According to the United Nations (UNICEF, 2022), “the latest report on the status of food and nutrition security shows that the world is moving backwards in efforts to eliminate hunger and malnutrition”. This report demonstrates an increase of “46 million since 2020, and 150 million since 2019”, reaching, in 2021, approximately 2.3 billion people in the world, in a condition of moderate or severe food insecurity (MARINI, 2022).

There are different aspects that must be considered to conceptualize food insecurity, in addition to those already mentioned. Amartya Sem (1999 apud BELIK and CAPACLE CORREA, 2013, p. 4), states that “hunger is the lack of people’s ability to control, by legal means or right, access to purchase food”.

In this speech, Sem (1999 apud BELIK and CAPACLE CORREA, 2013), explains that it is not just about buying food, since individuals need to have the financial conditions to do so; there must be an offer of these, since the absence of supply causes another serious phenomenon, which consists of hidden hunger.

Oxfam Brasil (2021) defines the classification related to food insecurity, in three levels: mild, when there is a lack of food motivated by seasonality; moderate, which is the limitation of the available variety or quantity of nutritional quality foods; acute, when there is the absence of meals for one or more consecutive days.

Thus, it is observed that food insecurity consists not only in the lack of adequate food, but also in the misery of certain groups of people without purchasing power; it also refers to the lack of food supply that meets the basic needs of citizens, and, thus, food insecurity reaches its peak, which is chronic hunger (BELIK and CAPACLE CORREA, 2013).

In 1943, the United Nations promoted the 1st. Hot Springs Food Conference, in the United States, with the intention of fighting hunger through an effort between nations, addressing “the complexity of food production and marketing flows” (BELIK and CAPACLE CORREA, 2013, p. 5 ).

At that moment, at the end of World War II, it was necessary to gather a joint force among the different countries, for the reconstruction of nations and protection of global society. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) was born, in which 44 nations participated, with the aim of promoting measures to combat world hunger (BELIK and CAPACLE CORREA, 2013).

The names of the conferences have been modified over time: in 1970, the United Nations (UN) established the concept of Food Security, an expression that was replaced in 1996 by the World Food Summit (BELIK and CAPACLE CORREA, 2013).

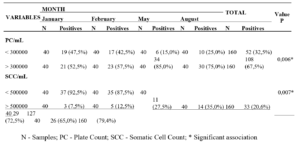

In turn, in 2020 the Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI) was launched, based on the union between different sectors interested in acting to guarantee global Food Safety, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Formation of the GFSI

Chart 1 presents the main tasks of the GFSI and what is not part of its scope and objectives.

Table 1. GFSI Commitments and Actions

| WHAT GFSI DOES | WHAT THE GFSI DOESN’T DO |

| Recognizes food safety management programs based on the GFSI Benchmarking Requirements. | Develops policies for retailers, manufacturers or certification program owners (CPOs). |

| It brings together a global network of food safety experts. | Conducts any accreditation or certification activity. |

| Drive change on strategic issues through multi-stakeholder projects. | Has any food safety program or standard, or conducts training. |

| Has involvement outside the scope of food safety, such as animal welfare, the environment or procurement ethics. |

Source: GFSI (2019, p. 5).

In 2021, the Food Systems Summit (CSA)[2] was held, considered the first of three important international conferences promoted by the United Nations (UN), to address topics such as: hunger, climate and biodiversity (BELIK and CAPACLE CORREA, 2013).

Despite the grandeur of bringing together the largest number of countries to debate and act on the problem, the fact is that, regardless of the name given to the meeting between nations, the aforementioned 1996 Summit established an agreement with a defined target by 2015, for the reduction by 50% of the total number of “hungry” people, that is, there was a need to reduce the total number of severely food insecure/undernourished people globally by 400 million (BELIK and CAPACLE CORREA, 2013).

The big question that arises is that the growth of the world population, especially in the poorest countries, aggravates the total number of people in food insecurity. In addition, even if the proposed 50% reduction was adopted internally (that is, an individual and internal target to be adopted by each of the participating countries) instead of being a global target, as in fact it ended up being proposed, such numbers would never be reached, as explained by Belik and Capacle Correa (2013).

The Global Food Security Index (GFSI), an index that allows measuring the food security of 113 countries, including Brazil, is a type of study developed by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), which provides data on food security in different regions , based on three criteria: access, availability and quality, and food safety (AISI, 2020).

A fourth factor was also pointed out, which would be the risk factor, with regard to the resilience capacity of different countries, in relation to adverse weather events and the natural resources existing in each region (AISI, 2020).

3.2 THE WORLD HUNGER NUMBERS

It is estimated that there are currently “10 million children under the age of five who suffer from acute malnutrition”, in addition to millions of people without food on a daily basis, a problem that has significantly worsened due to the Covid-19 pandemic (OXFAM BRAZIL, 2021).

In addition to these numbers, data tabulated by Unicef (2022) show that, worldwide, food insecurity is worsening alarmingly:

- 2019: 782 million food insecure (8% of world population);

- 2020: 828 million people are food insecure (9.3% of the world’s population);

- 2021: About 2.3 billion people in the world (29.3%) were food insecure;

- Gender inequality in food insecurity continued to increase in 2021, i.e. 31.9% of women globally were moderately or severely food insecure, compared to 27.6% of men. This represents a difference of more than 4 percentage points, compared to 3 percentage points in 2020;

- 2020: An estimated 45 million children under the age of 5 suffer from acute malnutrition, the most severe form of malnutrition, which increases the child’s risk of death by up to 12 times;

- 149 million children under age 5 were stunted in growth and development due to chronic lack of essential nutrients, while 39 million were overweight;

- 2030: Future projections: It is estimated that approximately 670 million people (8% of the world’s population) will still be facing food insecurity.

In turn, the White House (2022a) reports the situation in different countries:

- Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) – doubled the number of food insecure people between 2014 and 2020, from 90 million;

- Venezuela – in view of the political and humanitarian crises, there was an increase of 1/3 of the population in food insecurity, and an increase to 50% of signs of malnutrition in children under 5 years old;

- Honduras – as a result of the pandemic and hurricanes Eta and Iota, the total number of food insecure people doubled in 2021.

3.3 AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION

Different factors interfere in the production/supply of certain commodities, which are “products of agricultural origin or mineral extraction, in the raw state or with a small degree of industrialization, produced on a large scale and intended for foreign trade” (EPSJV, n.d.). Still, according to the EPSJV portal (n.d.), commodity prices are defined by national and international demand, as is the case of the main Brazilian commodities, which are: coffee, soy, wheat and oil.

Thus, if it is a fact that “food security is linked to food production, that is, to the ability of the agricultural sector to meet people’s food needs” (FUNDAÇÃO CARGILL, 2022), one must also consider the existence of the many aspects related to it, as is the case with questions related to agricultural production, which, in turn, must be combined with the reduction of food waste. It should also be mentioned that production spaces are becoming smaller and smaller, requiring the reformulation of planting and cultivation areas (OXFAM BRASIL, 2021).

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimates that 30% of world food production is lost annually between post-harvest and sale itself (OXFAM BRASIL, 2021).

Food waste is an aspect that greatly aggravates food insecurity. Marini (2022), brings a ranking of the 10 countries that waste the most food, including Brazil, whose estimated loss is “27 million tons of food, which is equivalent to 35% of the country’s entire production”, while “14 million Brazilians go hungry”, according to the Akatu Institute (2020).

In turn, food waste in the United States, pointed out by Forbes Magazine, through the article by Sorvino (2022), states that “every year, US$ 400 billion ends up in landfills and, as they reduce corporate profits, the companies can treat them as tax deductible”.

At the largest US supermarket chain, Kroger, “food waste accounts for about 4% of the nearly $140 billion (R$757 billion) in annual sales of the 2,800-store chain, or about $5, 6 billion (BRL 30.28 billion)” (SORVINO, 2022).

In the same article, Sorvino (2022) informs that local grocery stores have “an annual level of food waste of 5% to 7% of the products” they distribute. These are alarming data that were presented in the Forbes Magazine article:

“A dor fica muito maior e, portanto, a necessidade de uma solução torna-se muito maior”, diz McCann. Estima-se que uma mercearia, ou médios supermercados EUA, destruam entre US$ 5.000 e US$ 10.000 (R$ 27.000 e R$ 55.000) em comida por semana. Até recentemente, a maioria das mercearias e fornecedores de alimentos não sabia quanto estava jogando fora. Quaisquer que sejam as ineficiências que assolem o sistema, acabam sendo pagas pelos compradores que, segundo McCann “é cobrado no preço que o consumidor paga” (SORVINO, 2022).

Another factor that compromises global food security lies in the “dependence of several countries on food imports for their basic needs” (BELIK and CAPACLE CORREA, 2013, p. 5).

Among the factors that increase food shortages for vulnerable populations are: the international crisis; rising food prices; growth in demand for food, driven by increased consumption in emerging countries; the constant growth of the world’s population; the demand for raw materials for the production of biofuels; climatic shocks and the insufficiency of food stocks in global terms. Also noteworthy is the international financial crisis of 2007, which increased speculation in agricultural markets (BELIK and CAPACLE CORREA, 2013).

With the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic, all productive and commercial sectors had to face the temporary or permanent reduction/closure of their activities, and with agriculture and food production, it was no different. Necessary changes to the goods shipment protocols, changes in maritime routes, the shortage of workers, among other aspects that impacted the different areas of the production chain, including prices and supply (POSSAMAI and SERIGATTI, 2022, p. 15-16).

Two years later, and with the slow resumption of business, the recovery of the various sectors is still facing challenging times for its strengthening, given the numerous natural events caused by climate change, affecting food production. If we mention some of the occurrences in 2021, we can give as an example: the severe frosts that occurred in Brazilian plantations; floods and heavy rains on Chinese wheat crops; the extreme heat in India, which is the world’s second largest producer of wheat; conflicts in Eastern Europe, with the Russian invasion of Ukraine; events that, all taken together, represent a sharp reduction in the production and marketing of food around the world (POSSAMAI and SERIGATTI, 2022).

Unicef (2022) reports that Russia versus Ukraine, for example, are the “two largest global producers of basic cereals, oilseeds and fertilizers, about to disrupt international supply chains”; as a result, there is an increase in the prices of grains, fertilizers and energy, in addition to therapeutic foods, used in the care of children with severe malnutrition around the world.

Before being invaded, Ukraine would have shipped part of the previous harvest, but which, at present, has silos full of corn and barley, making it impossible to store a next harvest (end of June 2023), which could rot. Another problem faced is the lack of manpower, inputs and fuel to operate (POSSAMAI and SERIGATTI, 2022).

Russia, on the other hand, has been able to export its production, but may face a lack of seeds and pesticides, which it usually acquires in the European Union, which imposed severe sanctions, due to the invasion. These are issues that represent “serious risks to the global hunger crisis”, as explained by Possamai and Serigatti (2022).

3.4 REFORMULATION OF AGRICULTURAL POLICIES

According to Jaime (2020), there is a group of approximately 100 countries that are signatories to international treaties, which act in the defense and promotion of public policies related to the right that individuals have to healthy and dignified food. These are countries where there are laws and legal frameworks regulating this condition.

One can use, as an example, the United States, a privileged geographic region, where there is an abundance of food, whose economic development has allowed achieving a “high level of food security”, as defended by its Department of Agriculture (USDA) (LIMA, 2011, p. 69).

To ensure the effectiveness of food security, and despite being a nation whose population, for the most part, has high purchasing power, the US government has, among its laws, one that guarantees food and nutritional assistance programs to the population of low income, through its “United States Department of Agriculture” (USDA), whose investments reached approximately US$ 95 billion in 2010 (LIMA, 2011, p. 70).

However, the United States currently faces considerable domestic food insecurity challenges with approximately 26 million adults. While queues at food banks act to organize donations to the most needy, at a time when the North American economy is fragile in the post-pandemic, there are other factors to face, such as the increase in food prices, due to the Russian war against Ukraine (VEJA, 2022).

During the last conference, commitments were announced to reverse this situation, in addition to actions that already take place internally, such as, for example: advertising campaigns encouraging healthy eating to avoid illness; changes promoted in fast food chains, such as changes promoted in the children’s menu; among others (VEJA, 2022).

With regard to decarbonization, Moretti and Ferreira (2021, p. 4) report the green manifesto, a book by tycoon Bill Gates, which presents ideas for humanity to avoid the increase in climate disasters, in addition to the concept of Green Premium (GP), which consists of replacing fossil energy with clean energy in agricultural production.

According to the green manifesto, or GP, while fossil fuels are produced on a large scale and, therefore, are offered at low prices, the transition to clean technologies implies the development of inherent technologies to meet these needs (MORETTI and FERREIRA, 2021). That is, in addition to financial investments and specialized personnel, it will be necessary for people to become aware of the importance of this action, so that major disasters are avoided in the near future.

To promote the reduction of greenhouse gases, four lines of action were proposed in Gates’ book (MORETTI and FERREIRA, 2021):

- Capital mobilization for the reduction of greenhouse gases and promotion of Green Premiums (GPs), requiring investors to be willing to receive lower premiums and assume greater risks;

- Awareness of organizations regarding the reduction of carbon emissions, replacing raw materials with sustainable ones or buying credits to mitigate emissions;

- Promotion of research and development actions;

- Enabling the transition to clean technologies, identifying them or funding their development.

3.5 FROM PEASANTRY TO AGRIBUSINESS

According to Bernstein (2011, p. 60), several topics have been debated over time on the changes that have impacted agriculture in recent years, given the discussion of globalization, which are mentioned from now on:

- Trade liberalization, when there were numerous changes regarding global standards in the trade of agricultural commodities, reinforcing the already existing disputes involved, both inside and outside the World Trade Organization (WTO);

- Financialization of agricultural products, through the projections and speculation that arose regarding the prices of agricultural items;

- Almost suffocation of small farmers, from the withdrawal of government subsidies;

- Transformation of agriculture into global agro-input and agro-food corporations, through mergers between large companies, suffocating smaller ones;

- Emergence and implementation of new technologies in agricultural production chains, by the hands of the new giants of the sector, causing some phenomena, such as, for example, the revolution in the control of the food sales market;

- Molding of new technological practices, restricting practices and choices of smaller farmers and even consumers;

- Disputes between major organizations over the patenting of intellectual property rights of plant genetic material, in accordance with WTO provisions on Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights in Trade (TRIPS), and the issue of ‘biopiracy’ corporate;

- The new technical frontier: the genetic engineering of plants and animals (Genetically Modified Organisms – GMO) which, together with specialized monoculture, contributes to the loss of biodiversity;

- The new profit frontier: the production of biofuels, dominated by agribusiness corporations, with public subsidies in the USA and Europe, and its effects on the world production of grains for human consumption;

- The health consequences, including increased levels of toxic chemicals in ‘industrial’ grown and processed foods, and nutritional deficiencies in diets based on ‘junk food’, fast food and processed foods; the increase in obesity and obesity-related diseases, as well as the continuation and possible increase in hunger and malnutrition;

- The environmental costs of all of the above issues, including the levels of energy consumption and carbon emissions involved in ‘industrializing’ the growing, processing and selling of food – such as transporting food over long distances from the producer to the consumer, and the high cost of products transported by air;

- All questions related to the ‘sustainability or not’ of the current global food system: its continued growth or extended reproduction, together with observed trajectories.

3.6 AGRICULTURE 5.0

According to Brito (2019, p. 46), “the digital transformation has arrived for real and should change the way we produce food today, (…) and that will guarantee the survival of almost 10 billion people in the world in 2050, according to the United Nations (UN)”.

As president of the Board of Directors of the Brazilian Association of Agribusiness (ABAG), Brito (2019), pondered about agriculture 4.0. Brito’s speech (2019) brings important explanations for a better understanding of what digital transformation in agriculture means: he reports the “agritechs”, in which the United States invested approximately US$ 5 billion.

For TOTVS (2021), agribusiness was already rehearsing, in 2021, a major change in its methods, processes and demands, through the implementation of information technologies, “to enhance production (…) and (… ) maximize the quantity of products”. TOTVS argues that the objective of agriculture 5.0 is “to encourage the use of innovative technologies, such as robotics and Artificial Intelligence, together with data analysis, to maximize agricultural productivity”.

In other words, agriculture 5.0 is precision agriculture, which is based on data and technological resources, which allow evaluating and improving food production under a new focus, consisting of: “contributing to public health; expand productive capacity; make agriculture a pillar of sustainability in the world; move agriculture to the next level, deepening the use of data to make operations more profitable” (TOTVS, 2021).

Brito’s (2019) explanation means that

(…) entre outras providências, ao investir na realização de testes para desenvolver novas tecnologias, lançamento de satélites e uso de drones para a captura de dados, gerando nos computadores, imagens do campo a partir de dados organizados, que permitem rastrear os produtos durante a cadeia de suprimentos. Equivale a dizer que se trata da redução de custos e aumento da produtividade das lavouras por meio da inteligência artificial.

In turn, the Agrishow portal (2022) explains that “agriculture 5.0 is the latest generation of agricultural production models, responsible for promoting the fifth revolution in the sector”, with the main focus on increasing gains in “productivity, profitability and sustainability”, set referred to as the main pillars of Agriculture 5.0. This is a system that adopts different technologies for agribusiness production systems, including: robotics (biotechnology), machine learning and Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Still, according to Agrishow (2022), it is an important change from agriculture 4.0, when machines were still used on a daily basis, since in version 5.0 the drones inspect production, sending the information collected from sensors and data to computers. IoT (Internet of Things) devices, processing data and providing analysis so that managers can make the best decisions.

Massruhá et al. (2020), refer that the projection on the global scenario for 2050 is critical, listing several aspects that generate a lot of concern, all of them growing: the population that can reach nine billion people; scarcity of land and water for planting and human subsistence; proportion and regularity of extreme weather events; decrease in agricultural productivity in different countries, among others.

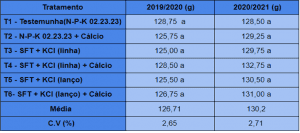

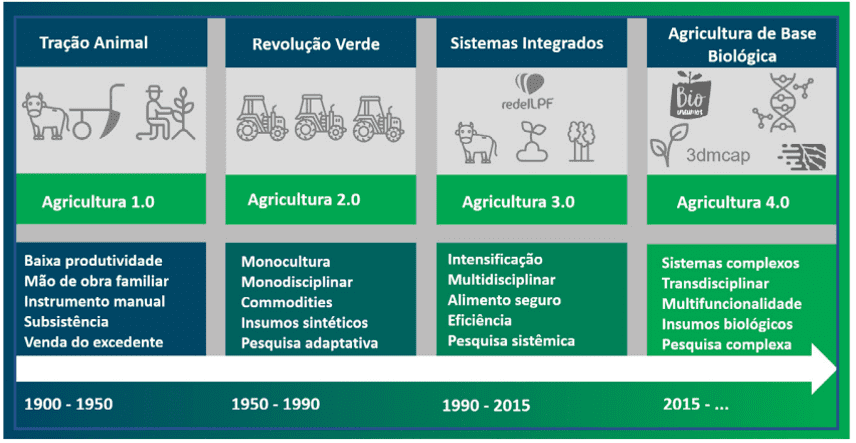

In summary, to approach Agriculture 5.0, it is important to analyze the timeline, during which the daily practices of agriculture evolved, as summarized by TOTVS (2021):

- Agriculture 1.0: The first step in agriculture was to define itself as a means of nourishing ancient populations. Over time, people reduced their nomadic movements to settle near rivers and lakes, however, their need to plant for their subsistence made them migrate in search of land that would allow planting. It was a phase in which the plantations belonged to the families or the nobles, who took over the peasants’ work, which was completely manual;

- Agriculture 2.0: starting from the Industrial Revolution, when steam engines appeared and then the invention of automobiles with their combustion engines, work on scale emerged, which, in planting, was translated into the use of animals to pull the plows, making life a little easier for the workers;

- Agriculture 3.0: also known as the Green Revolution, it began in the mid-twentieth century in the United States and spread throughout the world. It consisted of the use of new technologies and techniques for agriculture, among them: the means of accompanying the pace and growth of demand, following the wave of industrialization. It was a time when the use of fertilizers, pesticides and High Yield Variety (VAR)[3] seeds was adopted. It resembles the renewal of rural management;

- Agriculture 4.0: Reflecting industry 4.0, through the use of digital technologies, it has enabled improvements in crop control, pest anticipation and data guidance, in order to promote better solutions for the harvest.

For a better understanding of the evolutionary stages of agriculture, Figure 2 demonstrates these phases.

Figure 2. Phases of the evolution of agriculture

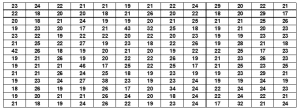

With regard to the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), listed in 2015 by the United Nations (UN), in order to lead governments, companies and societies towards a more sustainable and inclusive world, aiming to overcome political challenges , environmental and economic, were considered instruments to promote greater equity, dignity among people and environmental preservation. Among the 17 suggested SDGs, Massruhá et al. (2020, p. 21), explain that:

- SDG 2: related to the reduction/elimination of hunger, it aims to increase agricultural production in general, to mitigate hunger around the world;

- SDG 6: with regard to the conservation of drinking water and providing sanitation to all populations, it aims to improve agricultural irrigation in general;

- SDG 8: regarding the need for all individuals to have the right and the need in itself to work and produce in order to survive, it aims to promote actions that actually improve the production and survival conditions of small rural producers and family farmers, through the expanding access to information;

- SDG 9: with regard to industrial conditions for innovation and infrastructure promotion, it aims to provide support and/or improvement of production chains;

- SDG 11: on the distinctions between rural and urban life, aims to support their integration in a sustainable manner;

- SDG 12: regarding responsible consumption and production, aims to establish controls on crops, in order to avoid food waste and, therefore, reach the greatest possible number of needy people;

- SDG 13: with regard to climate-related issues, it aims to promote actions to mitigate major and aggravating risks that may further harm events that already occur, especially in reducing greenhouse gas emissions in livestock activities;

- SDG 14: on the cultivation of aquatic organisms, aims to protect and guarantee the improvement of aquaculture production;

- SDG 15: regarding land use, it aims to monitor and map the use of land cover and sustainable agricultural production;

- SDG 17: regarding the dissemination of information that optimize and modernize agricultural production processes, it aims to implement partnerships between these agents.

Since part of them is related to agriculture, Figure 3 demonstrates their potential for effectiveness.

Figure 3. Sustainable development goals related to agriculture

In turn, new technologies provide benchmarking for the quantity and quality of planting. According to the Agrishow portal (2022), some of its advantages stand out:

- Improvement of production and use of inputs;

- Productivity growth;

- Decreased risk of losses from pests, weather events or natural disasters;

- Reduction of negative impacts on the environment;

- Increase in producer income, from larger-scale production and productivity;

- Use of technological support to overcome the lack of technical capacity of professionals.

3.7 AGRICULTURAL POSSIBILITIES IN THE PROMOTION OF FOOD SECURITY

According to Evgenievich (2020), the significant increase in the prices of bread, rice, corn, vegetable oils, legumes and other basic items was pointed out by FAO. In response to this situation, different governments have defined internal temporary measures, such as: export quotas and price controls; tariff reduction for food imports; elimination of taxes and subsidies on agricultural production; to improve the domestic supply of basic products. Meanwhile, other countries reformulated their export quotas, like the “main rice exporters, including Egypt, India and Brazil, banned its export abroad”.

In turn, the World Bank announced, in May 2022, a “support program for agriculture, with a fund of US$ 30 billion, for the next fifteen months” (POSSAMAI and SERIGATTI, 2022, p. 16).

In the United States, on the occasion of the White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition and Health, President Joe Biden declared, on September 28, 2022, that he intends to end hunger in the American population by the end of this decade. Among the practical actions he will take are: introducing meal coverage to Medicare (local health system); incentive directed to the industry regarding the reduction of sodium and sugar; expansion of nutritional research (CASA BRANCA, 2022b).

Now, with regard to tackling world hunger, and, in addition to the existing fronts, Santoro (2022), describes how agricultural production can also collaborate, listing the following aspects, based on the use of Green Premium (GP):

- Use of line sensors: coupled to the seeders, generating planting maps in real time and informing the percentage of uniformity of double lines and failures;

- Seed distribution systems: allow to improve seed distribution uniformity and, even, to work with more than one hybrid model at the same time;

- Independent line systems: collaborate in the correction of the top up at the headlands and crop closures, allowing the distribution of fertilizer and reducing excessive expenses with seeds and inputs;

- Line pressure regulator: used abroad, it serves to replace the pressure springs of the seeders with a pneumatic system, to guarantee the automatic regulation of the pressure of the lines that is exerted under the ground, with adequate variation to the conditions of the soil and crop.

4. CONCLUSION

Over time, agribusiness has played a very significant role in the world economy, given the numerous advances achieved by agriculture. At present, agribusiness is experiencing a unique and unprecedented moment of transformation, requiring new investments in order to enable agricultural production to effectively collaborate to guarantee food security in the world, as well as the reduction of hunger and poverty.

Currently, agriculture arrives in its 5.0 version, through which innovative resources are used, such as artificial intelligence, which allows the increase of production in the field, reduction of general costs and improvement in the quality of the cultivated products, thus optimizing the decision-making, which results in extra benefits, such as: the reduction of environmental impacts and improvements in the connection between producer, administrator, operators and agronomists.

In this new phase, decisions are taken based on artificial intelligence and the automation of agricultural machinery, boosting the profits of investors in this sector. These are results that can benefit different countries interested in the production necessary to alleviate hunger in different places, given the gains in productivity, profitability and sustainability.

What can be seen from the literature, as well as from practical experiences, is that Agriculture 5.0 consists of a revolution for agribusiness, but that still requires improvements in the internet in the field, investments in research and in the development of new low-cost technologies for producers, tax incentives, provision of agricultural credit and personnel qualification, for the formation of specialized technical teams.

REFERENCES

AGRISHOW DIGITAL. Agricultura 5.0: o que podemos esperar dela? Agrishow Digital, mar. 2022. Disponível em: https://digital.agrishow.com.br/tecnologia/agricultura-50-o-que-podemos-esperar-dela. Acesso em: 16 nov. 2022.

AVICULTURA INDUSTRIAL – AISI. Segurança Alimentar: Estudo aponta que Brasil é o que mais se destaca em qualidade e segurança dos alimentos na América Latina. Avicultura Industrial, abr. 2020. Disponível em: https://www.aviculturaindustrial.com.br/imprensa/estudo-aponta-que-brasil-e-o-que-mais-se-destaca-em-qualidade-e-seguranca-dos/20200409-092230-y123. Acesso em: 22 nov. 2022.

BELIK, Walter; CAPACLE CORREA, Vivian Helena. A Crise dos Alimentos e os Agravantes para a Fome Mundial. Mundo Agrário, vol. 14, n. 27, 2013. Disponível em: http://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/art_revistas/pr.5945/pr.5945.pdf. Acesso em: 15 nov. 2022.

BERNSTEIN, Henry. A dinâmica de classe do desenvolvimento agrário na era da globalização. Dossiê Ciências Sociais e Desenvolvimento. Sociologias, v. 13, n. 27, ago. 2011. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-45222011000200004. Acesso em: 16 nov. 2022.

BRITO, Marcello. A agricultura do futuro chegou. Agroanalysis, vol. 39, n. 11, p. 46, 2019. Disponível em: https://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br/ojs/index.php/agroanalysis/article/view/80827/77178. Acesso em: 16 nov. 2022.

CASA BRANCA. Informativo: Governo Biden-Harris anuncia compromissos para promover Segurança Alimentar no Hemisfério Ocidental. Embaixada dos EUA e consulados no Brasil, jun. 2022a. Disponível em: https://br.usembassy.gov/pt/informativo-governo-biden-harris-anuncia-compromissos-para-promover-a-seguranca-alimentar-no-hemisferio-ocidental/. Acesso em: 22 nov. 2022.

CASA BRANCA. Na Assembleia Geral das Nações Unidas, o presidente Biden anuncia US$ 2,9 milhões em financiamento adicional pra fortalecer a Segurança Alimentar. Embaixada dos EUA e consulados no Brasil, set. 2022b. Disponível em: https://br.usembassy.gov/pt/na-assembleia-geral-das-nacoes-unidas-o-presidente-biden-anuncia-us-29-milhoes-em-financiamento-adicional-para-fortalecer-a-seguranca-alimentar/. Acesso em: 22 nov. 2022.

ESCOLA POLITÉCNICA DE SAÚDE JOAQUIM VENÂNCIO – EPSJV. Commodities – definição. Escola Politécnica De Saúde Joaquim Venâncio, Fiocruz, s.d. Disponível em: https://www.epsjv.fiocruz.br/commodities-definicao. Acesso em: 15 nov. 2022.

EVGENIEVICH, Kononov Dmitry. Crise Mundial de Alimentos: Causas e Possíveis Consequências. Azowo, jul. 2020. Disponível em: https://azowo.ru/pt/provod-vvgng/uhudshenie-prodovolstvennogo-snabzheniya-i-vvedenie-prodovolstvennoi/. Acesso em: 16 nov. 2022.

FUNDAÇÃO CARGILL. Qual a diferença entre segurança alimentar e segurança do alimento? Alimentação em Foco, jan. 2022. Disponível em: https://alimentacaoemfoco.org.br/o-que-e-seguranca-do-alimento/. Acesso em: 29 nov. 2022.

FUNDO DAS NAÇÕES UNIDAS PARA A INFÂNCIA – UNICEF. Relatório da ONU: Números globais de fome subiram para cerca de 828 milhões em 2021. Unicef, jul. 2022. Disponível em: https://www.unicef.org/brazil/comunicados-de-imprensa/relatorio-da-onu-numeros-globais-de-fome-subiram-para-cerca-de-828-milhoes-em-2021. Acesso em: 22 nov. 2022.

GASPARI, André Luiz. Desperdício de alimentos no varejo e os programas de reaproveitamento alimentar – o caso Bompreço Chame-Chame e o prato amigo. Monografia (Bacharelado em Ciências Econômicas) – Universidade Federal da Bahia. Salvador, 2001.

GLOBAL FOOD SAFETY INITIATIVE – GFSI. Safe food for consumers, everywhere. Global Food Safety Initiative, 2019. Disponível em: https://mygfsi.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/GFSI-General-Presentation-PT.pdf. Acesso em: 17 nov. 2022.

INSTITUTO AKATU. O desperdício de alimentos no mundo e no Brasil. Instituto Akatu, 2020. Disponível em: https://akatu.org.br/novopf/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/desperdicio-de-alimentos-no-brasil-e-no-mundo.pdf. Acesso em: 16 dez. 2022.

JAIME, Patrícia Constante. Pandemia de COVID19: implicações para (in)segurança alimentar e nutricional. Ciênc. Saúde coletiva, vol. 25, n. 7, jul. 2020. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232020257.12852020. Acesso em: 15 nov. 2022.

KEPPLE, Anne Walleser; SEGALL-CORRÊA, Ana Maria. Conceituando e medindo segurança alimentar e nutricional. Ciênc. saúde coletiva, vol. 16, n. 01, 2011. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232011000100022. Acesso em: 23 nov. 2022.

LIMA, Thiago. A Nova Lei de Segurança de Alimentos dos Estados Unidos e suas possíveis externalidades para o comércio internacional. Boletim de Economia e Política Internacional IPEA, n. 7, p. 69-78, jul./set. 2011. Disponível em: http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/bitstream/11058/4578/1/BEPI_n7_novalei.pdf. Acesso em: 22 nov. 2022.

MASSRUHÁ, Silvia Maria Fonseca Silveira; LEITE, Maria Angelica de Andrade; LUCHIARI JUNIOR, Ariovaldo; EVANGELISTA, Sílvio Roberto Medeiros. A transformação digital no campo rumo à agricultura sustentável e inteligente. Emprapa Agricultura Digital. Parte do livro. 2020. Disponível em: https://www.embrapa.br/busca-de-publicacoes/-/publicacao/1126214/a-transformacao-digital-no-campo-rumo-a-agricultura-sustentavel-e-inteligente. Acesso em: 16 nov. 2022.

MARINI, Gina. No Dia Mundial da Alimentação, uma reflexão sobre a segurança alimentar. Agência de Notícias da Indústria, out. 2022. Disponível em: https://noticias.portaldaindustria.com.br/artigos/gina-marini/no-dia-mundial-da-alimentacao-uma-reflexao-sobre-a-seguranca-alimentar/. Acesso em: 22 nov. 2022.

MORETTI, Celso Luiz; FERREIRA, Tiago Toledo. O manifesto verde de Bill Gates e a agricultura de baixo carbono no Brasil. Revista de Política Agrícola, ano 30, n. 01, p. 3-6, jan./mar. 2021. Disponível em: https://www.alice.cnptia.embrapa.br/alice/bitstream/doc/1131959/1/O-manifesto-verde.pdf. Acesso em: 15 nov. 2022.

OXFAM BRASIL. Descubra o que é segurança alimentar e qual sua importância. OXFAM Brasil, abr. 2021. Disponível em: https://www.oxfam.org.br/blog/descubra-o-que-e-seguranca-alimentar-e-qual-sua-importancia/. Acesso em: 22 nov. 2022.

POSSAMAI, Roberta; FELIPPE SERIGATI. Felippe. Crise alimentar no mundo.

AgroAnalysis, jun. 2022. Disponível em: https://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br/ojs/index.php/agroanalysis/article/view/88064/82807. Acesso em: 10 nov. 2022.

SANTORO, Marcelo. Como a agricultura 5.0 vai impulsionar seu trabalho na lavoura. Blog da Aegro, jan. 2022. Disponível em: https://blog.aegro.com.br/agricultura-5-0/. Acesso em: 16 nov. 2022.

SORVINO, Chloe. Desperdício de alimentos custa bilhões de dólares aos contribuintes dos EUA. Forbes, jul. 2022. Disponível em: https://forbes.com.br/forbesagro/2022/07/desperdicio-de-alimentos-custa-bilhoes-de-dolares-aos-contribuintes-dos-eua/. Acesso em: 16 dez. 2022.

TOTVS. Agricultura 5.0: Os impactos da tecnologia aplicada no setor. TOTVS, jul. 2021. Disponível em: https://www.totvs.com/blog/gestao-agricola/agricultura-5-0/. Acesso em: 16 nov. 2022.

VEJA. EUA anunciam plano audacioso para acabar com a fome até 2030. Veja, set. 2022. Disponível em: https://veja.abril.com.br/mundo/eua-anunciam-plano-audacioso-para-acabar-com-a-fome-ate-2030//. Acesso em: 23 nov. 2022.

APPENDIX – FOOTNOTE

2. Cúpula dos Sistemas Alimentares (CSA).

3. Variedades de Alto Rendimento (VAR).

[1] Graduated in Bachelor of Administration, from ULBRA, Universidade Luterana do Brasil-RS, Postgraduate in Logistics from Instituto Camilo Filho, Teresina-PI. ORCID: 0000-0002-8632-5468.

Sent: January, 2023.

Approved: January, 2023.