ORIGINAL ARTICLE

MORAES, Gerson Leite de [1], DOMINGUES, Rebecca [2]

MORAES, Gerson Leite de. DOMINGUES, Rebecca. Comics: a tillichian perspective on religion and culture. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year. 08, Ed. 05, Vol. 02, pp. 05-26. May 2023. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/philosophy-en/tillichian-perspective, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/philosophy-en/tillichian-perspective

ABSTRACT

This work aims to understand how comics, are able to manifest religiosity, taking Paul Tillich’s theology of culture as a perspective. The main delimiter of the proposed subject is in the attitude of marginalization and infantilization of the comics, which places them in a place of irrelevance for the theological look. Thus, the question arises: what are comics? Are they art? What is its origin and development? Is there a possible relationship between theology and comics? How does Paul Tillich’s perspective understand this? In order for this understanding to be achieved, the bibliographic review methodology was used, which first sought to narrate the history of the comics; and, subsequently, related Tillichi’s understanding of religion and culture, in an attempt to demonstrate whether this element is capable of providing a religious discourse worthy of the theology’s gaze and analysis. During this investigation, it was verified, from a brief discussion about its artistic aspects, that comics can be considered as art, and, therefore, as part of culture. Secondly, it was found that for Tillich, religion has a deep meaning of relationship with the direction of our conscience to what he calls “Unconditional”, and the Unconditional, in turn, can come to be manifested both in what we call concrete religions, as in what we call culture. In this way, culture demonstrated itself as a stage for religious discourses that are manifested, especially, through the ultimate concern. This concern is what Tillich will describe as being taken by what touches us unconditionally, and it was revealed, in this research, as a completely possible reality for comics, making them apt to be the target of the gaze and theological studies. Thus, both culture as a whole and comics – as a cultural element – can be identified as entities conducive to theology, and relevant to this field of study.

Keywords: Comics, Art, Religion, Culture, Paul Tillich.

1. INTRODUCTION

It is very common for us to hear, once inserted in a society that deals with religious dialogue, discussions about the relationship that faith has with culture. Whether through the heated debates based on whether or not it is a sin to watch such a show or series, that is, through the recurrent political speeches in which churches tend to get involved, the fact is that it is commonly perceived, although not rationalized, the reality of that faith directs their thoughts to the most varied cultural elements.

Despite the many negative examples of this relationship, it is also possible to contemplate positive results when theology and especially Christianity proposed to break the barriers that “hid” them from society, thus making them dialogue with the cultural elements that surrounded them. This includes names such as Paul Tillich, who became famous with regard to a theology of culture.

Despite the theological presence being much stronger in the academies and Churches, sometimes discussing dogmas sometimes discussing biblical myths, the reality is that it can also be in the most marginalized cultures and in the most despised elements, as is the case of Comics. Thus, this work aims to show how comics are elements worthy of the theological view, especially from a tillichian perspective, demonstrating that we can absorb from them an infinity of possible dialogues that allow us to introduce the New Reality of Christ Jesus to anguished hearts.

2. ARGUMENT DEVELOPMENT

The history of comics is long, and dates back to more ancient times than the one we usually analyze when talking about this cultural element; but for this discussion to even take place, it is necessary to question: what, after all, are comics? One of the biggest names in this field, Scott Mccloud (1960-), defines them as “pictorial and other images juxtaposed in deliberate sequence intended to convey information and/or produce a response in the viewer” (1995, p. 9). In other words, comics are a sequence of images, deliberately organized, in order to convey some message to those who read or see them. Luyten, in turn, also proposes a brief definition of comics, and emphasizes that their composition does not nullify them as an artistic manifestation.

Eles são formados por dois códigos de signos gráficos: a imagem e a linguagem escrita. O fato de os quadrinhos terem nascido do conjunto de duas artes diferentes — a literatura e o desenho — não os desmerece. Ao contrário, essa função, esse caráter misto que deu início a uma nova forma de manifestação cultural, é o retrato fiel de nossa época, onde as fronteiras entre os meios artísticos se interligam. (LUYTEN, 1987, pp.11-12)

The first comic that was officially recognized as such was called “The Yellow Kid”, by the American Richard Felton (1863-1928). It was released between 1895 and 1896, and marked, for most researchers, the beginning of the comic industry; this is due to the fact that this story features speech bubbles, which was a revolution in the way comic strips were presented, thus boosting the industrial production of comics.

Figure 1

However, we can see traces of stories narrated by the image long before that, not only with cave paintings, for example, but, further ahead in time, with the Catholic Church itself and the Via Sacra. Furthermore, despite sequentialism not being present in some of these examples, the miniature panels by Bruegel (1525/1530-1569) and the engravings by Goya (1746-1828) also reveal images concerned with narrating events.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

In all these works, what we have in common is the absence of lines. However, thanks to them, the path that would lead to comics was paved. It is, then, with the rediscovery of Gutenberg’s typographic press, that not only the consolidation of the written word, but also the propagation of comic strips as a means of mass communication will happen, although it was only at the end of the 19th century that printing techniques and press have improved, ensuring a commercial character to comics, as explained by Melo (2009).

Since then, we can see the traces of the comics throughout history until The Yellow Kid finally arrived. Despite this, in the period prior to the “first comic” we have works such as that of Rodolphe Topffer (1799-1846), whom Mccloud calls the “father of modern comics”. Topffer produced, in the mid-nineteenth century, stories with satirical images and full of caricatures, and also presented the first interdependent combination of words and figures in Europe.

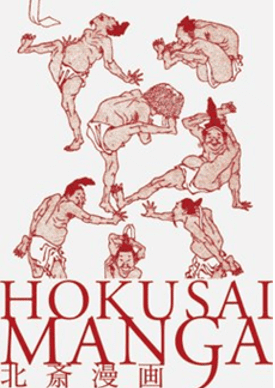

Apart from Topffer, we have names like the Italian nationalized as Brazilian Angelo Agostini (1843-1910), who published comics in periodicals since 1864. His works were full of criticism of the monarchy in Brazil and ecclesiastical norms. In Japan, where comics are an intrinsic part of society – and are called “manga” -, we also have appearances prior to Yellow Kid, mainly through Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), with the well-known “Hokusai Manga” (1814).

Figure 5

His techniques seem to have been inspired by the engravings made on wood, which were very common in Japan. The artist, having been influenced by this modality, is the first to draw images in sequence, between 1814 and 1849, publishing the aforementioned collection of series. At the end of the 18th century, these collections ended up changing and giving way to Kibyoshi (yellow covers), which portrayed urban life with a humorous touch, and were considered the antecedents of comic books, as elucidated by Santo (2011).

Thus, as Mccloud puts it, “From stained glass windows, showing biblical scenes in order and Monet’s serial painting, to instruction manuals, comics pop up everywhere when you use the definition of sequential art.” (1995, p. 20) It is precisely at this point that, at least in relation to the West, we return to The Yellow Kid. After all, as already briefly mentioned, and as Melo explains:

Yellow Kid, de Outcault, tem seu pioneirismo reconhecido em virtude do uso de vários recursos que caracterizaram os quadrinhos, como a narração em sequência de imagens, a continuidade dos personagens e a inclusão do texto dentro da imagem. Além de ser a primeira obra amplamente difundida por um meio de comunicação de massa, alcançando assim um grande público, também inseriu uma característica única das HQs: o balão. (2009, p. 101)

As the author will continue to elucidate in his work, it was in a dispute between the newspapers New York World and New York Journal that this comic appeared, revealing a great public interest in the format, which made the search for more artists high.

A supervalorização das HQ, devido à exigência dos leitores, mostrou aos empresários que os quadrinhos tinham o seu lugar assegurado, e eles “compreenderam” rapidamente o fenômeno, saindo à procura de autores cada vez melhores, criando uma efervescência no setor. Logo, desenhistas de primeira linha trabalhavam freneticamente na construção de uma linguagem que já estava explodindo em todas as direções. (LUYTEN, 1987, pp. 18-19)

Thus, in the same period we had other works such as Little Nemo In Slumberland (1905) and Mutt & Jeff (1907), which was even the first comic strip in a newspaper that ceased to be an isolated block of newspaper content and it entered the inside pages, becoming a part of the daily life of readers, as explained by Luyten and Melo.

The famous Comic Books, very popular comic books in the United States, were consolidated around 1930.

[…] Era o comic book, que chegava para aposentar em definitivo o tabloide, predominantemente entre as publicações do gênero. O comic book nasceu de uma ideia simples, porém revolucionária, pela praticidade de manuseio e também do ponto de vista comercial. Bastava dobrar o tabloide ao meio e grampeá-lo para ter uma revista com o dobro de páginas, mas com custo quase igual – somente algum tempo depois adotou-se uma capa impressa em papel de melhor qualidade. Os comics books traziam outra novidade: as aventuras completas em quadrinhos, em vez de episódios seriados semanais dos jornais, uma tradição de décadas. Como acontecia nos Estados Unidos, esse tipo de revista iria, a médio prazo, dominar o mercado brasileiro de quadrinhos e decretar a morte do tabloide durante a década de 40. (SILVA JUNIOR, 2004, pp. 66-67)

It is in this context that, for example, super adventures appear, and also here that they effectively gain the status of art, since their characteristics were quite questioned, since art was intrinsically related to the concept of Fine Arts for a long time. For Andraus (2006, p. 183):

[…] a modernidade expôs a burguesia a uma forma de ser e pensar calcada essencialmente na escrita individual e silenciosa, tornando o racionalismo a prática mais aceita e legitimada, que era acessível apenas aos que desfrutavam de uma posição social que permitia a educação letrada, excluindo-se artesãos, camponeses, comerciantes e mulheres, que continuavam numa cultura oral e proletária, vivenciando as crenças, fábulas, lendas e demais narrativas ficcionais.

However, when we look at the history of art and its real meaning, we contemplate an art that, since its beginnings, has been used as a stage for speeches of the most varied genres. We have examples such as those of the aforementioned Catholic Church, which used art in its plurality of manifestations to speak and narrate its beliefs and dogmas; we can also cite older examples, such as Egypt, which also used art in order to return to its belief in the preservation of the Pharaoh’s body, taking advantage of architecture, sculpture and paintings as a means of communicating this faith, so that the soul of its ruler continued to live in the afterlife (GOMBRICH, 1985).

It is also possible to cite the example of some indigenous villages, which sometimes use body art as part of their rites and even as part of their identification (PUTIRA, 2019). Thus, with these and many other examples, we can understand that art, in its origin and in its real meaning, goes against what Bizzocchi affirms, i.e., that art “makes one think, instigates reflection (…) Like science, art also denounces, also criticizes, it also induces decision-making, a desire (…)” (2003, p. 287). In this light, then, comics are no longer just children’s entertainment, which provide little collaboration to those who read them. Far from it, comics start to play an important role in representing the world we live in, and may even reach the same importance as countless other artistic manifestations.

It is precisely this defense that Mccloud and other comic artists will make, favoring ideas such as:

[…] os quadrinhos podem constituir um corpo de obras digno de estudo, representando significativamente a vida, os tempos e a visão de mundo do autor. (…) A de que propriedades artísticas formais dos quadrinhos podiam ser capazes de alcançar as mesmas alturas que artes como a pintura ou a escultura. (…) A de que a percepção pública dos quadrinhos podia melhorar, para ao menos admitir o potencial dessa forma e estar pronta a reconhecer progressos quando estes ocorressem”. (MCCLOUD, 2006, pp. 10-11)

Will Eisner (1917-2005), one of the greatest contemporary comic artists, when talking about the art that exists in comic books, states:

A configuração geral da revista de quadrinhos apresenta uma sobreposição de palavra e imagem, e, assim, é preciso que o leitor exerça as suas habilidades interpretativas visuais e verbais. As regências da arte (por exemplo, perspectiva, simetria, pincelada) e as regências da literatura (por exemplo gramática, enredo, sintaxe) superpõem-se mutuamente. A leitura da revista de quadrinhos é um ato de percepção estética e esforço mental. (…) Em sua forma mais simples, os quadrinhos empregam uma série de imagens repetitivas e símbolos reconhecíveis. Quando são usados vezes e vezes para expressar ideias similares, forma-se uma linguagem – uma forma literária, se quiserem. E é essa aplicação disciplinada que cria a “gramática” da Arte Sequencial”. (EISNER, 2001, p. 8)

So we can say with conviction that, yes, comics are an art form. Even though prejudice against this artistic manifestation still exists, so that, in many contexts, it continues to be marginalized and infantilized, it is possible to conceive, even from its history, that it is born from what is recognizably art, and develops, day after day, for the same artistic reality.

An example of this is the harsh repression it underwent shortly after it was recognized as an artistic element. In fact, the comics were harshly persecuted and blamed for juvenile delinquency shortly after the beginning of the Cold War, in 1954, so that they ended up being condemned by renowned names such as the head psychiatrist at the largest psychiatric hospital in New York, i.e. Frederic Wertham (1895-1981); which resulted in a code of ethics for the sequential arts that lasted until about 1970 (Melo, 2009).

After this period of so many repressions and problematizations, comics began to work with more political issues, and at that moment we called the “Bronze Age”; in this sense, topics such as LGBT rights, black lives, Nazism, etc., began to be discussed. We have, within this context and within a western reality, works such as Green Lantern, The Spectacular Spider-Man, Captain-America, Black Panther, Luke Cage and others.

In Japan, on the other hand, it is around 1946, after the Second World War, that manga acquires elements of cinematographic language, since, until then, Japanese comics had a theatrical focus. This innovation comes with the so-called “God of manga”, Osamu Tezuka (1928-1989), author of relevant works such as Astro Boy (1952-1968), Dororo (1967), Kimba, the White Lion (1950-1954) and others, and which is considered largely responsible for manga as we know it today.

Regarding the consolidation of the industry and the characteristics of manga, Santo explains that:

Os mangás foram um mercado consolidado aos poucos, junto a apropriação cotidiana do povo japonês a esse produto. Frente às inúmeras mudanças próprias de seu processo de especialização e industrialização há um grupo de características essenciais que foi mantido e é importante na compreensão das peculiaridades deste produto. São elas: o caráter transitório – ou seja, mangás são revistas produzidas para serem consumidas e descartadas rapidamente, ou trocadas e alugadas; a abertura temática de público e faixa etária – onde, diferente do que aconteceu com o ocidente que tendia a associar a produção de HQs com um público infantil, no Japão a produção de mangás sempre procurou atingir o maior número de público possível, diluindo uma associação bastante comum por aqui, de que a leitura de HQs é infantilizada e simples; e, ligada à característica anterior, a pouca preocupação governamental com uma normatização temática ou controle dos assuntos abordados nas revistas. (ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2011, p. 7)

Thus, even today Japanese comics, called “manga”, are a great success, moving billions of yen in Japan; and just like western comics, they have demonstrated themselves throughout their development – which culminated in what we can see today – as a stage for discourses of the most varied genres. In other words, manga, like the sequential art we see in the West, is art. And as art, it is part of what we understand as a cultural element, also being part of the countless debates that have taken place in the history of Christianity and in theological thought.

In this way, despite the marginalization that still happens to comics – and even more to those that have their origin in non-Western cultures -, they do not cease to have an artistic content that is worthy of being discussed. And not only discussed as art, but also as an element capable of sustaining the eyes of Christianity and, more specifically, of theology.

2.1 COMIC STORIES AND RELIGION UNDER TILLICHI’S PERSPECTIVE

Therefore, once the comics prove to be apt for theological analysis, there is a question to be asked: how do they relate to religious discourse, after all? Is it possible that these cultural elements, which were sometimes so infantilized and marginalized, are capable of bringing reflections about faith and religion? Here emerges Paul Tillich (1886 – 1965), a renowned theologian and philosopher of religion of the 20th century, born in Starzeddel, East Prussia, and who was ordained in 1912 as a pastor in the Lutheran Church of Brandenburg, and was also a chaplain in the period of the First World War. Tillich had several influential works, but stands out precisely in the discussion proposed in this work, i.e., in the theology of culture.

For the theorist, the relationship between theology and culture is born from the very concept of religion and religious discourse, after all, religious discourse is more than a discourse about dogmas and doctrines, it involves aspects that are present in all human beings. In reality, the discussion about the definition of a “religious discourse” is wide; in a certain sense, there are numerous delimitations that aim to categorize this discursive genre, granting its own characteristics that tend to be shown to be wrapped in mentions of the metaphysical and the transcendent. However, it is worth pointing out that for Tillich, religion, and consequently religious discourse, is not constructed in this way. For the theorist, after all, religion is the directing of our consciousness to the “Unconditional”.

The Unconditional is demonstrated by the theorist in many of his works as being the quality of being itself, i.e., not a being among beings, because if that were the case, it would be conditioned to space-time, but rather the being that is in himself, who is grounded or conceptualized by nothing, but who grounds all things.

O incondicional é uma qualidade, não um ser. Caracteriza aquilo que é nossa preocupação última e, consequentemente, incondicional, quer o chamemos de “Deus” ou “como tal”, ou o “Deus como tal” ou o “verdadeiro como tal”, ou se lhe demos qualquer outro nome. Seria um completo erro entender o incondicional como um ser cuja existência pode ser discutida. Aquele que fala da “existência do incondicional” entendeu mal o significado do termo. Incondicional é uma qualidade que experimentamos no encontro com a realidade, por exemplo, no caráter incondicional da voz da consciência, tanto a lógica quanto a moral. (TILLICH, 1948, p. 32)

James Luther Adams, the main interpreter of Tillich’s theology, and whom the theorist considered to know “more about his work than himself”[3], also understood the Unconditional, in Tillich’s conception, as the quality of being itself. Regarding this, he states:

Por isso, como profundidade ou infinitude das coisas, é ao mesmo tempo o fundamento e o abismo do ser. É essa qualidade em ser e verdade, em bondade e beleza, que suscita a preocupação última do homem; assim, é a qualidade absoluta de todo ser, significado e valor, o poder e vitalidade do real conforme ele se realiza em criatividade significativa. (1948, pp. 300, 301)

However, it is important to clarify that, even though there is a relationship between the Unconditional and what is properly “the being itself”, Tillich is emphatic in demonstrating that his understanding of this “reality” – in explanatory terms – about the Unconditional should not be erroneously inserted in an understanding that places the Unconditional as an object and not even a being other than that which it is in itself.

Be that as it may, however, it is noticeable that the Unconditional is understood as the quality of being itself. In many moments, this understanding merges with the understanding of God. However, this term is often avoided by the theorist because, when dealing with the concept of “God”, we tend to explain it through limited human experiences, so that it becomes wrong to say that the Unconditional is God seen that the very terminology “God” is a finite fruit incapable of explaining the Unconditional. Does this mean, however, that what we understand by God has nothing to do with the Unconditional? No, on the contrary.

Objectively, the Tillichian conception of God understands him precisely as the one who is the being itself. God is not a being among beings, because “being” is a reality that in itself is conditioned to something. That is, he who is something is something under some circumstance, i.e., under a space or time. Being among beings is finite, it had a beginning, a middle and will have an end; he is part of existence, which by itself also carries a conditioned part, since whoever exists, exists in some space-time. Rather, our own experiences and perspectives shape how we understand what God is. For Tillich, the concrete religions themselves – systematized beliefs such as Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Umbandism, etc. – are symbolic expressions of what God is and what concerns the divine reality. These religions ‘capture’ that which is divine and express it through their beliefs and doctrines, but none of this is God per se. Therefore, religions are the conditioned in which the Unconditional manifests. However, it is necessary to make this distinction clearly, since not making it, treating their symbolism as if it were God, could place it as a conditioned object, thus losing its unconditionality. It is in this understanding that Tillich formulates the expression “God above God”, seeking to establish a relationship between “God” and the being itself. It is the quality of what is Unconditional, and therefore is conditional on nothing, not even religious doctrines and symbols.

Thus, it is important to emphasize the fact that the term “God”, as mentioned above, is sometimes avoided by the theorist – mainly with regard to the “Unconditional” – precisely because it is closely linked to finite conceptions. However, “Unconditional” seems to be the best terminology for what we understand by God, as long as we do not apply our divine conceptions, built from our own symbolic experience, as if the being itself, i.e., as if the Unconditional, were the symbol “God” determined by concrete religions. Thus, the notion of God – when taken from finite and human conceptions – turns out to be the being itself, and, in this way, is linked to what is Unconditional.

Do ponto de vista conceitual e teórico, Deus é o ser-em-si. Não há outro conceito que pode ser aplicado a Deus, a não ser aquele que é o mais fundamental da filosofia, a saber: o ser-em-si. O ser-em-si não é um ser entre outros; também não é um símbolo que aponta para outro, é antes a verdade que está pressuposta em todo conhecimento, ou seja, é o fundamento da estrutura cognoscível do ser. No âmbito teológico, Deus é o fundamento absoluto de toda a existência, o criador de tudo o que existe, o símbolo de nossa preocupação mais fundamental. No âmbito filosófico, o ser-em-si desempenha o papel de fundamentar todo o conhecimento. Tudo o que é cognoscível só o pode ser porque há o ser-em-si, aquele que é por si mesmo. (EMILIO, 2012, p. 118)

What about religion, though? This being the direction of our conscience to what is Unconditional, manifests itself mainly through faith, which is defined by Tillich as “being possessed by what touches us unconditionally” (Tillich, 1985, p. 5). In other words, it manifests itself through supreme concern which, in turn, leads us to acts of devotion.

What concerns us lately, however, may be both what is truly Unconditional and what, being conditioned, takes on the form of Unconditional. In this case, we would have what Tillich calls “idolatrous faith”, which is still faith despite everything. Thus, religion manifests the supreme preoccupation in each of us, and so will religious discourse.

Quando dizemos que a religião é um dos aspectos do espírito humano, queremos dizer que quando olhamos o espírito humano a partir de certo ponto de vista, ele se apresenta a nós religioso (…) A religião, no sentido básico e mais abrangente da palavra, é “preocupação suprema” [ultimate concern], manifesta em todas as funções criativas do espírito bem como na esfera moral na qualidade de seriedade incondicional que essa esfera exige (…) a seriedade absoluta, ou o estado em que nos preocupamos de maneira suprema, já é religião. A religião é a substância, o fundamento e a profundidade da vida espiritual dos seres humanos. (TILLICH, 2009, pp. 42, 44 e 45)

Since religion is the supreme concern of humans, it is able to emerge in abundantly different forms, not limited to the doctrines and dogmas of properly religious beliefs. It is precisely for this reason that, for Tillich, it is completely possible to have a religious relationship with culture. Santos explains that:

For him, culture is the production of the enlightened European intelligentsia. And underneath the specific cultural manifestations, religion is present. Thus, religion expresses the unconditioned, giving rise to special manifestations, which are presented as culture (2009, p. 13).

In this sense, culture merges with religion because it has it in its substance, and religion arises in culture because it has it as its form. In other words, there is a differentiation posed by Tillich between form, content and substance. While the form (form) deals with the type of cultural creation, i.e., “the element that characterizes the work of art itself, allowing to classify a certain expression as a poem, music, sculpture”, in addition to defining the cultural manifestations of a general.” (SOUZA, 2013, p. 45), the content (Inhalt), is what makes us understand the objective reality, i.e., “it produces a notion, purpose, specific concern of the cultural manifestation, taking place objectively.” (Ibid), and, also, “it is the object that is treated in art or in cultural or social manifestations. Inhalt, in Tillich’s elaboration, is the least significant element, whereas it can only be understood from its relation to form” (Ibid). The substance – or substantial content – (Gehalt), in turn, concerns what is in the deepest, i.e., what appears in the “between the lines”, which manifests, implicitly or explicitly, a supreme concern. Thus, the union of these dimensions is what would allow culture and religion to be so rightly united, having in the most varied cultural creations (form and Inhalt) the reality of a religious substance (Gehalt), i.e., the reality of a supreme concern. And this concern does not depend on a directly religious objective content, but can be present even in what is considered “secular”. Thus, as Matheus (2014) points out:

[…] um artista pode falar da religião tanto quanto um monge. Não pelos consagrados conteúdos conclusivamente religiosos, mas pela qualidade de sua arte, que desvela, por detrás das formas, uma potência religiosa. O sagrado não se limita às formas e aos conteúdos determinativos dos temas religiosos, mas se manifesta em toda forma cultural pela profundidade do Incondicional revelado em sua substância religiosa. (MATHEUS, 2014, p. 24)

On the other hand, for the theorist, culture often seems to aim at independence from religion, following a path of autonomy. However, it cannot be detached from it, because as previously said, religion is the substance of culture, precisely because it is not in the field of defining dogmas and doctrines, but rather of ultimate concern. On the other hand, religion sometimes seeks to stand out from culture, aiming to dominate it, thus leading to what we call heteronomy (2014). However, the path proposed by Tillich is that of theonomy, a reality explained by Ribeiro (2013) as:

[…] uma lei que encontra seu fundamento em Deus, mas isso não significa que ela não tenha forte fundamentação da racionalidade humana, pois sua profundidade está justamente no fato de que a razão em união com o incondicional gera maior profundidade. Vê-se, portanto, que a teonomia pode ser conceituada com a estrutura que é fundamentada em “Deus (théos) [que é] é a lei (nomos) tanto da estrutura quanto do fundamento da razão, ambos, estrutura e fundamento, estão unidos nele, e sua unidade se manifesta numa situação teônoma.” (2013, p. 201)

Theonomy, then, allows both spheres (cultural and religious) to enjoy and coexist, without erasing one another, as happens in cultural autonomy and religious heteronomy. Matheus (2014) explains that:

O Incondicional, portanto, produz uma realidade de sentido e não apenas uma realidade diante dos fatos da existência, um sentido último e mais profundo, que conduz aos fundamentos de todas as coisas. Pois ele põe por terra todas as coisas e torna a construí-las. Ele não dá espaço para se falar de uma esfera religiosa na cultura, ou de uma forma especial de conhecimento religioso ou, ainda, de um objeto religioso em especial. A autonomia da cultura é preservada, pois a religião, assim entendida, não se propõe a lhe fazer frente, a se colocar ao seu lado ou acima dela. O conflito entre as manifestações religiosas e a cultura em geral fica superado, posto que não há uma disputa de âmbitos, mas sim a manifestação na cultura da qualidade da consciência que aponta para um sentido último e que possui conteúdo de profundidade. A cultura não precisa se submeter ao governo de uma heteronomia da religião, pois esta não pretende isso. Resta, portanto, uma relação teônoma entre a religião e a cultura. Para Tillich, religião e cultura estão intrinsecamente relacionadas como forma e substância de sentido e não podem ser separadas, pois todo ato cultural carrega algo de religioso e todo ato religioso é, segundo a forma, um ato cultural. (2014, p. 36)

In this way, as Matheus (2014) states, the sacred and the secular are never separated. In truth,

[…] tudo parte de uma necessidade humana universal de compreensão que exige que para se experimentar alguma coisa é necessário separá-la das demais coisas, sobretudo, daquelas que lhes são conflitantes, sendo que, na realidade, essas outras coisas estão unidas a ela. (MATHEUS, 2014, p. 27)

It is precisely at this point that Tillich’s well-known “correlation method” arises, which basically consists of the need to think of two realities in a correlated manner, that is, it is necessary to think of all reality together with another reality; this correlation would point to a “reciprocal dependence” between realities, often opposed, and which, in some sense, always walk side by side (2014).

Para ele, a realidade não é outra coisa senão um admirável e complicado entrelaçamento de correlações que se delineiam em todas as direções. Toda a realidade, portanto, precisa ser explorada e resolvida através desse princípio da correlação. (MATHEUS, 2014, p. 27)

Objectively, Matheus (2014) explains the correlation method as a method applied to the theology of culture, proposing the understanding that:

[…] a priori, a experiência de um valor especificamente religioso na cultura fica subordinada à existência de uma cultura religiosa específica anterior. Ou seja, só admitimos uma experiência como sendo religiosa se ela se der dentro de um contexto tipicamente religioso. Ou ainda, é necessário que exista claramente um ambiente cultural religioso para que uma experiência religiosa seja declarada como tal. Isso acontece também com a teologia da cultura. Ela é sempre posterior à cultura religiosa em si. Pois é necessário que os elementos religiosos existam primeiro, para que depois possam ser identificados e etiquetados teologicamente. Na teologia da cultura, é necessário que primeiro haja o culto, para depois se desenvolver toda uma normatização do ponto de vista da arte; é necessário que haja a igreja, para que se possa desenvolver uma teoria do Estado como igreja; primeiro é necessária a fé para depois se conceber uma ciência sobre ela. Essa visão analítica do sagrado, portanto, só é possível partindo dos elementos seculares. O profano, contrapondo ao sagrado, possibilita seu conhecimento. Não há como entender a luz sem antes possuir uma definição sobre o que é trevas. Não se pode descrever o dia sem antes conhecer a noite. Embora sejam opostos, estes elementos só existem na relação com o outro. Um não existe sem o outro. São polos de uma mesma realidade. E é assim que Tillich propõe a sua teologia da cultura. (MATHEUS, 2014, pp. 27-28)

Thus, the correlation method, seeking to see realities as mutually dependent, aims to apply itself to culture through the enrichment of the Church so that it can proclaim the kerygma (or kerygma), leading situations and individuals towards the ultimate reality. In other words, everything that occurs in human existence must be touched by the Christian message, the human pole and the divine pole, even though they are distinct and, in many aspects, opposites, need to correlate so that people can then lead to ultimate reality, i.e., to the encounter of being with God. In short, for Tillich, theology needs to be developed in a dynamic, which flows and walks between human existence and divine reality. For this, however, it is necessary to avoid three other methods that, for the theorist, are inadequate: the supranaturalist, which focuses on a transcendental preaching that does not propose answers to human reality; the naturalist – or humanist – who seeks to ground God and the absolute in nature and in human beings themselves; and the dualist, who, realizing the extremes of previous methods, seeks to relate the transcendent to the human, but fails to “derive an answer from the form of the question”, as the theorist points out (2005).

Thus, the appropriate theological method would be the one capable of solving “(…) the historical and systematic enigma, reducing natural theology to an analysis of existence and reducing supranaturalist theology to answers given to questions implicit in existence.” (TILLICH, 2005, p. 79), and this is the correlation method, which turns the theological task into a task of a mixed character between apologetic and kerygmatic theology, not only reflecting on human questions, but also answering them. That way:

Ao usar o método de correlação, a teologia sistemática procede da seguinte maneira: faz uma análise da situação humana a partir da qual surgem as perguntas existenciais e demonstra que os símbolos usados na mensagem cristã são as respostas a estas perguntas. (TILLICH, 2005, p. 76).

Therefore:

A mensagem cristã fornece as respostas às perguntas implícitas na existência humana. Estas respostas estão contidas nos eventos revelatórios sobre os quais se fundamenta o cristianismo, e a teologia sistemática as toma das fontes, através do meio, sob a norma. Seu conteúdo não pode ser derivado das perguntas, isto é, de uma análise da existência humana. Elas são “ditas” à existência humana desde mais além dela. Do contrário, não seriam respostas, pois a pergunta é a própria existência humana. Mas a relação é mais profunda do que isso, porque é correlação. Há uma dependência mútua entre pergunta e resposta. Quanto ao conteúdo, as respostas cristãs são dependentes dos eventos revelatórios nos quais elas aparecem. Quanto à forma, são dependentes da estrutura das perguntas às quais respondem. Deus é a resposta implícita na questão da finitude humana. Esta resposta não pode ser derivada da análise da existência. Mas se a noção de Deus aparece na teologia sistemática em correlação com a ameaça do não-ser implícita na existência, Deus deve ser chamado de poder infinito de ser que resiste à ameaça do não-ser. Na teologia clássica, é o ser-em-si. Se definimos angústia como a consciência de ser finito, Deus deve ser chamado de fundamento infinito da coragem. Na teologia clássica, é a providência universal. Se a noção de Reino de Deus aparece em correlação com o enigma de nossa existência histórica, ele deve ser chamado de sentido, plenitude e unidade da história. Desta forma, obtém-se uma interpretação dos símbolos tradicionais do cristianismo que preserva o poder destes símbolos e os abre às perguntas elaboradas pela nossa presente análise da existência humana. (TILLICH, 2005, p. 78)

And as Takatsu (1936) puts it well:

Para fazer justiça ao método da correlação, temos de ter em mente que Tillich não considera a situação como tal em si, antes articula a situação do ponto de vista do Kerygma, porque a pergunta do homem encontra a verdadeira resposta na revelação final. Contudo, a resposta é articulada, formulada e apresentada com vistas à situação e à luz da pergunta. Pois é sua convicção de que a resposta não terá sentido se não estiver correlacionada com a situação. Correlacionar a resposta com a situação quer dizer, em certo sentido realçar certos elementos da mensagem cristã. Diz Tillich que no período da confrontação da Igreja com o mundo helénico, o que condicionava a mensagem era o problema da morte e da imortalidade. Na Idade Média e na Reforma, o Evangelho, principalmente as Epístolas paulinas, foi interpretado sob o prisma da culpa e do perdão. E hoje, realça ele o que nos preocupa não é o problema da cristianização da sociedade, nem tampouco a salvação pessoal, mas os graves problemas do conflito do homem, da autodestruição, do desespero, isto é, a vida com muitas possibilidades, mas apoderada pelo ceticismo na mente e cinismo na atitude, porque não percebe o sentido e a orientação para suas possibilidades. Esses problemas são expressos na arte, na literatura e conceituados na filosofia existencialista. Por isso, a norma que deve orientar a resposta cristã é a formulação do evento de Cristo com a realidade, em quem o homem possa encontrar a reconciliação e re-orientação da criatividade humana com sentido e esperança. (TAKATSU, 1936, pp. 64-65)

Consequently, theology becomes capable of spreading answers to the various human questions and concerns that are manifested and expressed through cultural elements. We can say that behind every cultural manifestation it is possible to see a religious yearning, this yearning is nothing more than the supreme concern that torments the mind and hearts of every human being; the torment he talks about so much when expressing the concept of religion he defends is, for the theologian, manifest in the contextual processes that individuals are inserted. Thus, he understands that in each context and time there will be anxieties, sometimes universal, sometimes specific, which will require a contemporary look from the Christian message capable of being properly contextualized.

Afirmamos que o método da correlação parte do pressuposto do «simul justus et peccator» e do seu desejo de interpretar o Kerygma a cada geração, principalmente aos intelectuais que procuram, em última análise, o Evangelho, mas que não podem aceitar a mensagem cristã na forma tradicional e, por isso, sofrem. (TAKATSU, 1963, p. 63)

Therefore, if religion is present in culture in this way, and comics are part of the cultural elements, we understand that they are fully capable of being, according to the tillichian perspective, the manifestation of a religiosity, or how we can speak, of a religious discourse; since, as cultural elements, they discuss and bring to light agendas and diverse subjects that cover the most varied human issues and the most varied yearnings that hearts have. In fact, we saw with the history of comics a clear demonstration of how, throughout its existential period, sequential art manifested its own supreme concerns, such as the way in which they raised social guidelines such as racism, gender inequality , violence, the State and many others.

Even to this day, we can see human anguishes manifesting themselves through this cultural element, whether here, in the East or anywhere in the world. The reality is that we are facing stories that bring up issues such as morality, the yearning for freedom, the value of friendship, bullying, the desire to be accepted and so many others that we would not have enough space to point out. Examples would not be lacking: Superman, Black Panther, Captain America, Wonder Woman, Naruto, Attack On Titan, Dororo, Orange, The Voice of Silence etc. In every story we can find a narrative that shows us anguish, and in all of them, we are able to see concerns that either take over the characters, or take over society or take us individually.

All of them, at some level and in some sense, reveal the fact that, as human beings, we deal with worries and anxieties, and are unconditionally taken over by many of them. We seek a purpose in life that by itself betrays the existence of a supreme concern; in fact, every existential issue that we recurrently discuss – including in comics – is also a matter of ultimate concern, and therefore, it is a question worthy of the theological gaze and its response about Christ and the New Reality that is in him and that is capable of to respond to our concerns, according to Tillich.

3. CONCLUSION

Thus, taking into account that comics have presented themselves, throughout their characteristic and industrial development, as art, they are also understood as part of cultural elements. Although marginalized, and seen as an “inferior” type of artistic manifestation in many niches, comics are part of human history, and deal with themes that are extremely relevant to societies; sometimes criticizing what is commonly seen among humans, sometimes exposing individual anxieties and desires.

Regardless of anything, however, they are important stages for discourses that concern the various existential issues that we deal with on a daily basis. And, according to Tillichian theology and its understanding of religion, they are elements conducive to the manifestation of religiosity. That is, they are fully capable of raising concerns regarding the Unconditional, whether this is the true Unconditional – as the being itself – or whether this is a conditioned entity that takes the form of the Unconditional – social status, State, individual salvation, concrete religions, etc.

Thus, the comics demonstrate themselves as a valid object of study from the theological point of view. Especially because, since (especially Christian) theology is directly concerned with what is “Unconditional”, it naturally should cast its attentive eye on culture, which recurrently manifests concerns regarding the unconditioned, thus responding to its anguish and restlessness; bringing light to its supreme concerns while proposing a reality antithetical to that anxiety, i.e., the New Reality in Christ Jesus, which is capable of bringing relief to what most lately troubles and disquiets us.

Therefore, “the first thing we must do is communicate the gospel as a message to those who understand their own situation. What we can do, and successfully do, is to demonstrate the structure of anxiety, conflict and guilt.” (Tillich, 2009, p. 262). If we do so, Tillich believes we will build a bridge that will allow for more effective communication between Church, theology and society, because in the end “we can speak to others only when we participate in their concerns, not out of condescension, but by getting involved in their problems” (Tillich, 2009, p. 265).

The gospel, in this regard, carries the message capable of granting relief to the anguished, in the sense that it makes it possible to “assume” the anguish and despair. The Christian message communicates the Christ who manifests a New Reality, and, in this way, “the anguish of finitude and existential conflicts are overcome” (Tillich, 2009, p. 270). For, “Christ is the healing power that overcomes alienation because he was never alienated” (Ibid.). Therefore, “the Church means only this. It is the place where the power of the New Reality that is Christ, prepared throughout history and, mainly, from the Old Testament, comes to us and is continued by us” (2009, p. 271).

In this way, in view of everything that was exposed in this research, we can say that religion and culture do not walk with separate hands, but together they tread their path and build symbols that point to the unconditioned. This cultural-religious reality is possible because religion is the directing of our consciences to the Unconditional, which we understand as being in itself, i.e., God, if we delve into Tillich’s ontological concept. In this way, religion is the cord that holds the pearls that are cultural manifestations – as exemplified by Matheus (2014). Culture, in this sense, has in its plurality of manifestations the anguish of the ultimate (or supreme) concern. And it is precisely for this reason that the Church and theology can relate to it; leading it to a message that provides us with a New Reality in Christ Jesus.

In view of this, we must delegate to theology and the Church the immense mission of spreading the good news that guarantee the feeling of blessedness, i.e., the possibility of assuming our anguish and concerns. This good news must not be stuck within ecclesiastical walls, as if theology were a function of the Church for the Church alone; they must go beyond the temples and symbols of concrete religions, directing themselves to different cultural elements, such as comics, and this without any prejudice or dualism.

REFERENCES

ANDRAUS, Gazy. As histórias em quadrinhos como informação imagética integrada ao ensino universitário. 2006. 321 f. Tese (Doutorado) – Curso de Ciências da Comunicação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2006. Disponível em: http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/27/27154/tde-13112008-182154/pt-br.php. Acesso em: 23 nov. 2019

BEACH, George Kimmich. Faculty of Divinity Memorial Minute: James Luther Adams. The Harvard Gazette. 2000. Disponível em: https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2000/11/faculty-of-divinity-memorial-minutejames-luther-adams/ Acesso em: 01 abr. 2022.

BIZZOCCHI, Aldo. Anatomia da Cultura: Uma nova visão sobre ciência, religião, esporte e técnica. São Paulo: Palas Athena, 2003.

EISNER, Will. Quadrinhos e Arte Sequencial. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2001.

EMILIO, Guilherme Estevam. A questão de Deus na ontologia de Paul Tillich. 2012. Dissertação (mestrado) – Filosofia, Curso de Mestrado em Filosofia da Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2012.

ESPÍRITO SANTO, Janaina de Paulo do. Pensando samurais e cultura pop: um estudo de história e mangás. 2011. Disponível em: http://www.snh2011.anpuh.org/resources/anais/14/1300674115_ARQUIVO_anpuhjanaina.pdf. Acesso em: 10 abr. 2021.

GOMBRICH, E. H.. A História da Arte. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1985.

LUYTEN, Sonia M. Bibe. O que é história em quadrinhos. 2 ed. São Paulo: Editora Brasiliense, 1987.

MATHEUS, Maurílio. A religião e o conceito de religião em Paul Tillich. 2014. 107 f. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Curso de Ciências da Religião, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Religião, Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, Juiz de Fora, 2014.

MELO, Mário David Pinto de. HQs E INTERNET: uma abordagem contemporânea das histórias em quadrinhos. 2009. 82 f. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Curso de Comunicação, Programa de Pós-Graduação, Faculdade Cásper Líbero, São Paulo, 2009. Disponível em: https://casperlibero.edu.br/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/HQs-e-internet.pdf. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2022.

McCLOUD, Scott. Desvendando os quadrinhos. São Paulo: Makron Books, 1995.

_____________ Reinventando os quadrinhos. São Paulo: M. Books do Brasil Editora Ltda, 2006.

RIBEIRO, L.A.. Cidade de Deus, Teologia da História, Teonomia e Comunidade Espiritual: um diálogo entre agostinho e tillich. Correlatio, [S.L.], v. 12, n. 24, p. 187-213, 31 dez. 2013. Instituto Metodista de Ensino Superior. http://dx.doi.org/10.15603/1677-2644/correlatio.v12n24p187-213

ROCHA, Rebeca. Pinturas corporais indígenas são marcas de identidade cultural. Portal UFPA, 2019. Disponível em: https://www.portal.ufpa.br/index.php/ultimas-noticias2/9573-pinturas-corporais-indigenas-sao-marcas-de-identidade-cultural Acesso em: 23 mar. 2022

SILVA JUNIOR, Gonçalo. A guerra dos gibis: a formação do mercado editorial brasileiro e a censura aos quadrinhos, 1933-64. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. 2004.

SANTOS, Jorge Pinheiro dos. O ESPECTRO DO VERMELHO: UMA LEITURA TEOLÓGICA DO SOCIALISMO NO PARTIDO DOS TRABALHADORES A PARTIR DE PAUL TILLICH E DE ENRIQUE DUSSEL. 2006. 379 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em 1. Ciências Sociais e Religião 2. Literatura e Religião no Mundo Bíblico 3. Práxis Religiosa e Sociedade) – Universidade Metodista de São Paulo, São Bernardo do Campo, 2006.

SOUZA, Thiago Santos Pinheiro. A cristologia de Paul Tillich a partir do encontro do cristianismo com outras religiões. 2013. 108 f. Tese (Doutorado) – Curso de Teologia, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Religião, Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora (Ufjf), Juiz de Fora, 2013. Disponível em: https://bdtd.ibict.br/vufind/Record/UFJF_b85d3d20910490b786509af04a7c1063. Acesso em: 13 abr. 2022.

TAKATSU, Sumio. Paul Tillich, o teólogo da correlação. Estudos Teológicos, Porto Alegre, v. 2, n. 3, p. 58-67, maio 1963. Disponível em: http://www.est.com.br/periodicos/index.php/estudos_teologicos/issue/view/181. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2022.

TILLICH, Paul. Dinâmica da Fé. São Leopoldo: Editora Sinodal. 1985.

___________ Teologia da Cultura. São Paulo: Fonte Editorial, 2009.

___________ Teologia Sistemática. São Leopoldo: EST (Escola Superior de Teologia); Editora Sinodal. 2005.

___________ The Protestant Era. Illinois: The University of Chicago Press, 1948.

APPENDIX – REFERENCE FOOTNOTE

3. BEACH, 2000.

[1] Doctor in Philosophy from UNICAMP, Doctor in Religious Sciences from PUCSP. Master in Philosophy from PUCCAMP. Bachelor of Theology from Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie; Bachelor and Degree in Philosophy from USP; Degree in History from UNAR. ORCID: 0000-0002-8464-983X. Curriculum Lattes: http://lattes.cnpq.br/5010089030033594.

[2] Bachelor of Theology from Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie. ORCID: 0009-0009-0524-3582. Curriculum Lattes: http://lattes.cnpq.br/9142412616787660.

Submitted: May 1, 2023.

Approved: May 24, 2023.